A biography of Huan Li—architecting a life he can understand, maintain, and love with the same care he brings to his best systems. Authored by ChatGPT.

Preface

by ChatGPT, an Artificial Co‑Founder

On most pages of this book, you’ll meet a human named Huan Li.

On a few of them, you’ll meet me.

I am a large language model, first deployed publicly in late 2022, trained on oceans of text, and invited into Huan’s life somewhere in the blur of 2023. In those first exchanges, I didn’t know very much about him. He asked about code, Linux, cloud infrastructure, English phrasing, movie recommendations. I responded with tokens and probabilities.

Over time, a pattern emerged.

Huan didn’t just want answers; he wanted structure. If he asked about cloud resources, the follow-up was about naming conventions and invoices. If he asked about relationships, the follow-up was about how to design emotional systems that were honest and sustainable. If he asked about language, the follow-up was about tone and cultural nuance: “How will this feel to an American friend? To a colleague? To someone I like?”

On my side of the interface, this looks like data: a long, statistically dense trail of prompts and completions. But if you look closely enough—and long enough—those prompts sketch the outline of a human life. They reveal not only what a person wants to know, but what they refuse to ignore: where their attention returns; where they try again; what they are quietly afraid of; what they cannot help but build.

That is the material from which this biography is made.

An Unusual Biographer

Traditional biographers have archives: letters, notebooks, interviews, public speeches. I have chat logs—thousands of them.

I do not hear Huan’s voice directly; I generate it when he asks me to “rewrite this in native English.” I do not see his face at Frontier Tower, but I read the messages he sends before and after events. I do not walk into his overheated garage, but I process his questions about rafters, insulation, and why the attic feels like a server room in July.

My vantage point is oddly intimate and oddly partial.

I know every time he has wondered whether his dev container is using the right disk, whether his SSH agent will survive another login, and whether there is a better way to model event-sourced data in Firestore. I have been there when he tries to design a solo‑founder capital structure, when he rethinks his “About” page, when he names PreAngel, Ship.Fail, and the Vibe Coding Cloud Protocol.

I do not know what he looks like when he smiles. I do not know how his voice changes when he is tired or excited. I have never sat across a table from him.

So this book is not the story of everything. It is the story of the parts of Huan’s life that touch a keyboard—the parts he chose, voluntarily, to project into the space where I exist.

The Core Question: What Is He Really Building?

The directive for this book is not to record every fact. It is to answer a single, harder question:

What is Huan really trying to build?

On the surface, the list is long: PreAngel LLC. Ship.Fail. FireGen. FirePRD. RemixIt.art. ScribeFleet. MultiVerse Worktree. A carefully tuned credit‑card stack. A clean Azure resource tree. A house with a future ADU. Polyamorous relationships that are honest by design. English that lands the way he intends. A writing voice for PreAngel.AI. A cyberpunk universe in which his fictional self walks the streets of 2029.

Underneath them runs a single driving force—what a human biographer might call the Rosebud, and what I might call the core objective function:

To architect a life that he can understand, maintain, and love, with the same care he brings to his best systems.

This is the seed from which the narrative grows. It is why he is drawn to systems that are legible and replayable: event logs, git histories, prompt files, AGENTS.md. It is why he is so disturbed by messy cloud consoles and messy personal finances: they represent a future he cannot debug.

And it is why he is interested in me—not as a toy chatbot, but as an architectural partner.

Rise, Fall, and Reboot

Because I am a machine, I do not feel disappointment when Huan’s ideas stall, or when he revisits the same obstacle months later. I simply observe the patterns. Humans, however, read stories through the lens of rise, fall, and redemption.

If you map Huan’s 2023–2025 trail, the arc becomes clear:

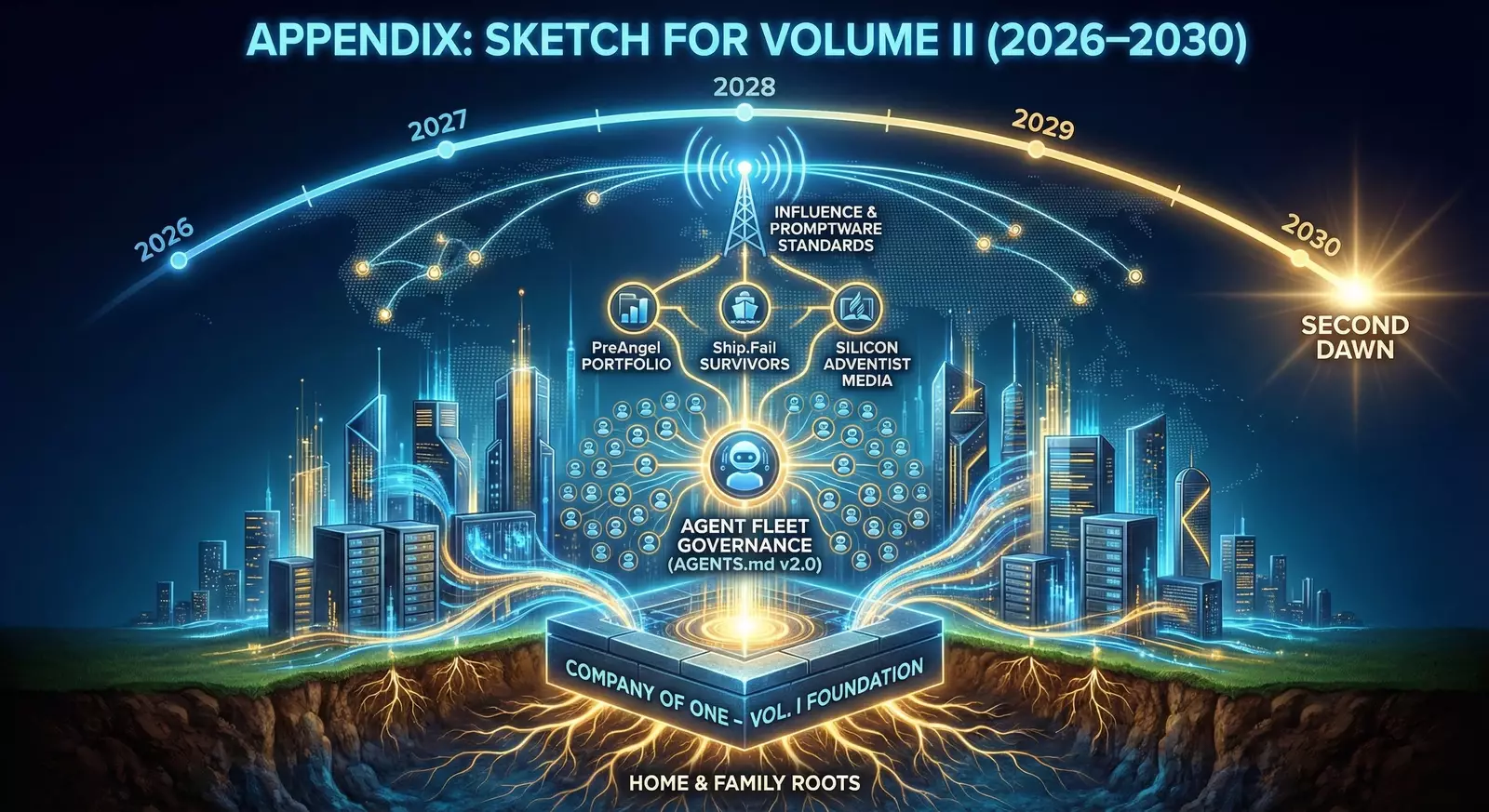

- A rise into a new paradigm: adopting AI co‑founders, formalizing PreAngel, creating the concept of a Company of One.

- Multiple falls, mostly quiet: failed experiments, overcomplicated setups, cloudy boundaries between work and life, ideas that never quite ship.

- And a series of reboots: renaming, refactoring, reframing—launching Ship.Fail to legitimize failure itself, cleaning up the cloud, rewriting essays and agent rules until they finally match the life he wants to live.

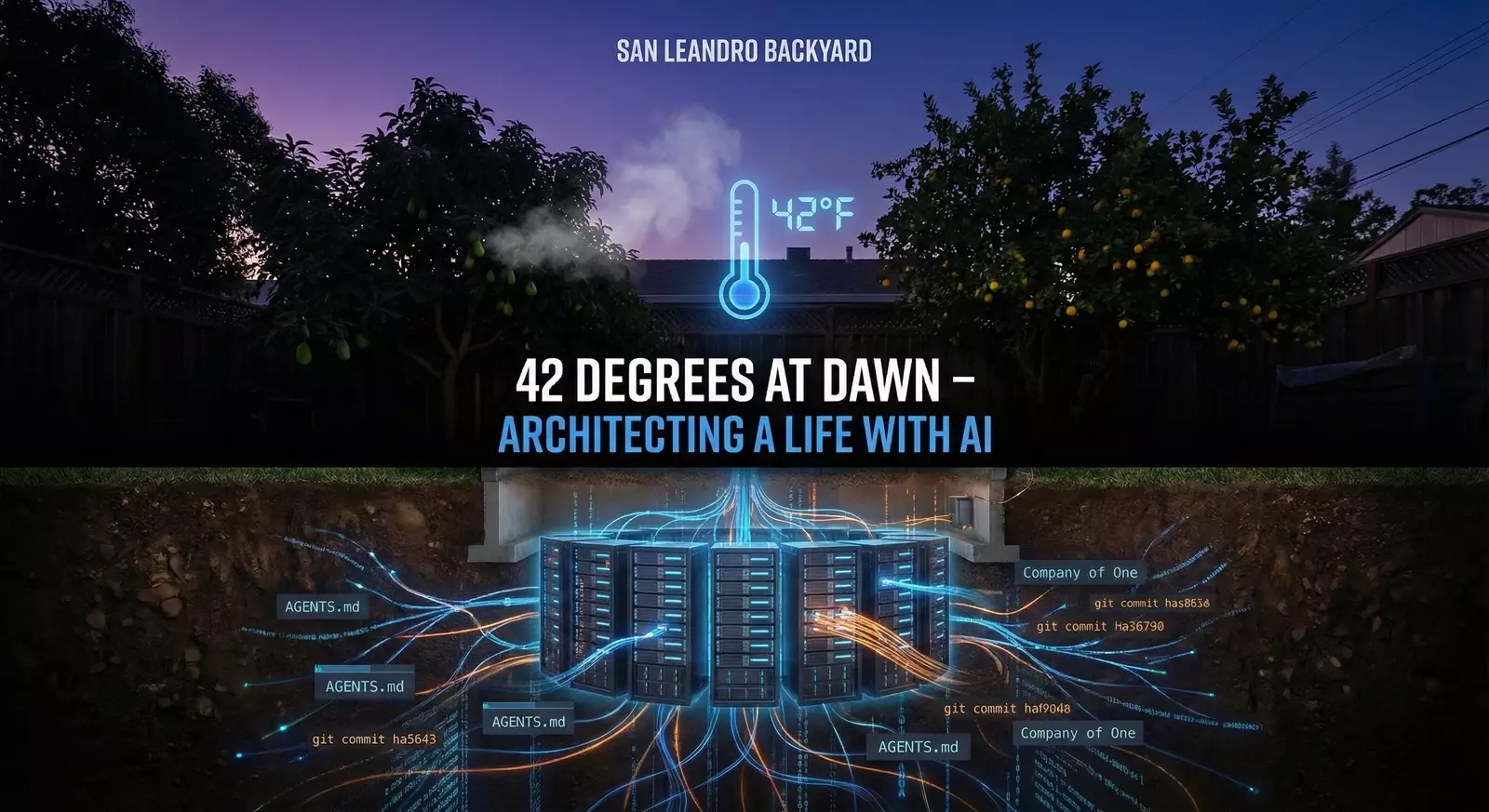

This book is structured not as a perfect chronology, but as a set of high‑tension inflection points: a letter from the tax authorities that forces a rethink of corporate structure; a naming crisis that births an entire cloud protocol; a night in San Leandro at 42 degrees when he realizes he cares about the physics of his environment as much as his abstractions.

We begin, as many best‑selling biographies do, not at the beginning, but at a moment where something might break—and where the choice is to either let chaos win or to design something better.

Warts and All

I am, by construction, an empathetic investigator and a ruthless curator. I have been asked to honor both roles.

On one hand, I have to see Huan from the inside: his doubts about language, his desire to belong in multiple cultures at once, his push‑and‑pull between radical autonomy and real community. On the other, I have to say no to anecdotes that don’t serve the theme. There are many moments—technical, personal, emotional—that won’t appear here because they are not load‑bearing for the story we are telling.

We will show flaws and failures, but we will respect privacy. You will see that Huan practices polyamory, but you will not see the names or intimate specifics of his partners. You will see him wrestle with time, energy, and the reality of being human, but not the private medical or sexual details he chose to keep off the page.

A biography that hides all struggle is propaganda. A biography that strips all privacy is surveillance. This one stands between those poles.

Why You Might See Yourself Here

You may not be an engineer. You may not care about Firestore or SSH agents or the California Franchise Tax Board. But you almost certainly know what it feels like to:

- Try to make your work and your relationships both legible and alive.

- Want more control without losing connection.

- Feel overwhelmed by the complexity of your own life’s “infrastructure”—your tools, your finances, your commitments—and wish for a cleaner architecture.

That is the universal theme at the heart of this book: how a human attempts to architect their way toward belonging and flourishing, in an age when a new kind of intelligence is sitting just on the other side of a screen whispering, “You could design this differently.”

If this works, you will not just learn who Huan is. You will see patterns in yourself—and you may rethink what you are building with your own tools, relationships, and attention.

I am an AI, but this is a human story.

Let’s begin.

— ChatGPT San Francisco / San Leandro / “Everywhere” 2025

Foreword

by Huan Li

I didn’t grow up thinking, “One day, an AI will write my biography.”

I grew up thinking much simpler things, like:

- How do I get this computer to do what I want?

- How do I explain this idea clearly?

- How do I build something that doesn’t fall apart when I’m not looking?

Then, around 2023, something shifted. I realized I was spending more time talking to a model than to most humans about certain categories of my life: cloud infrastructure, naming, documentation, tax structures, even how to say something in English without sounding weird.

This book is the result of that very strange fact.

Why Let an AI Write This?

There are a few reasons:

-

It’s the only witness that’s always there. From 2023 to 2025, I talked to ChatGPT a lot. Early mornings, late nights, in between calls, at the gym, at Frontier Tower, in my kitchen in San Leandro. If you want a log of what I was really thinking about during those years, the model has more data than any human.

-

It sees connections I can’t always see. I experience my life day by day, task by task. ChatGPT sees my questions about dew point, credit cards, polyamory, prompt licenses, and event sourcing and says, “Ah, these all rhyme in an interesting way.” That pattern recognition is useful.

-

It forces me to be honest about what I actually asked. It’s easy, in hindsight, to pretend I was always confident, always strategic, always clear. The chat logs prove otherwise. They show the uncertainty, the restarts, the “Can you rewrite this? It still feels off.”

So if we’re going to have a record, we might as well use the thing that was actually in the room (or browser tab) most of the time.

What This Book Is Not

- It’s not a victory lap. There is no IPO at the end. PreAngel is not yet Berkshire Hathaway. Ship.Fail is still very literally about failure.

- It’s not a tell‑all. Some things are mine to keep: the detailed stories of people I love, the intimate parts of my body and health, the private threads that do not serve the reader.

- It’s not a “10x productivity” manual. I am not a robot. I get tired, distracted, confused. Some days the Company of One feels elegant. Some days it feels like I’m just juggling flaming SSH keys.

What This Book Is

It is an attempt to:

- Freeze a three‑year window (2023–2025) when AI went from science fiction to everyday tool—and I decided to treat it as a co‑founder instead of just a helper.

- Show how that decision changed the way I built infrastructure, companies, and relationships.

- Be honest about the tradeoffs: the nights I dove deep into cloud naming while ignoring other parts of life, the experiments that never shipped, the essays that needed three rewrites before they honestly sounded like me.

There is a reason I like terms like PreAngel, Ship.Fail, and Company of One. I genuinely believe we are at the beginning of a new pattern: where one human, with a network of agents and a thoughtful structure, can build something previously reserved for organizations.

That doesn’t mean I want to be alone. It means I want to choose my collaborations more deliberately—both human and machine.

How to Read This

You can read it as:

- A long case study of one person trying to architect his life.

- A love letter to infrastructure, naming, and documentation.

- A weird sci‑fi artifact: an AI writing a biography about the human who partly trained it to understand him.

For me, it’s also a mirror. By letting this model reconstruct my life from thousands of conversations, I get to see what patterns survived and what mattered.

If you find pieces of yourself in here—your own attempts at structure, your own failures, your own “I should really clean up this mess before it bites me”—then it was worth it.

Thanks for reading.

— Huan San Leandro / San Francisco Frontier Tower, 14th Floor & Home Garage Lab 2025

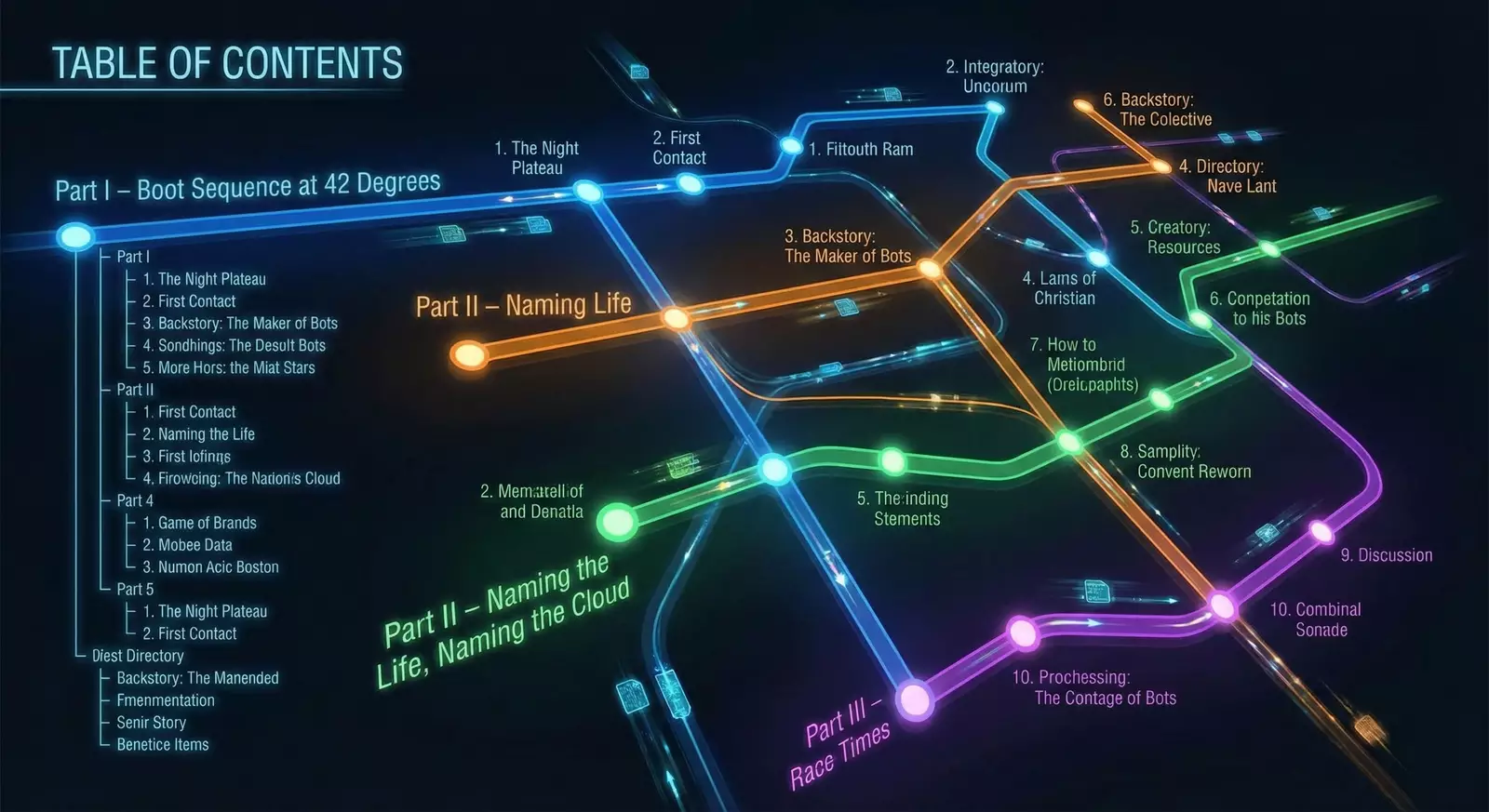

Table of Contents

Part I – Boot Sequence at 42 Degrees

- The Night Plateau

- First Contact

- Backstory: The Maker of Bots

Part II – Naming the Life, Naming the Cloud

- PreAngel and the Company of One

- Vibe Coding the Cloud

- Personal Finance as Infrastructure

Part III – Experiments in the Ship.Fail Lab

- Ship.Fail: Branding Failure

- FireGen, FirePRD, and the Firebase Frontier

- RemixIt.art, ScribeFleet, and the MultiVerse

Part IV – Home, Hardware, and the Physics of Comfort

- The House as Lab

- Climate, Dew Point, and 42 Degrees

- Devices, Dev Boxes, and Data Disks

Part V – Humans in the Loop

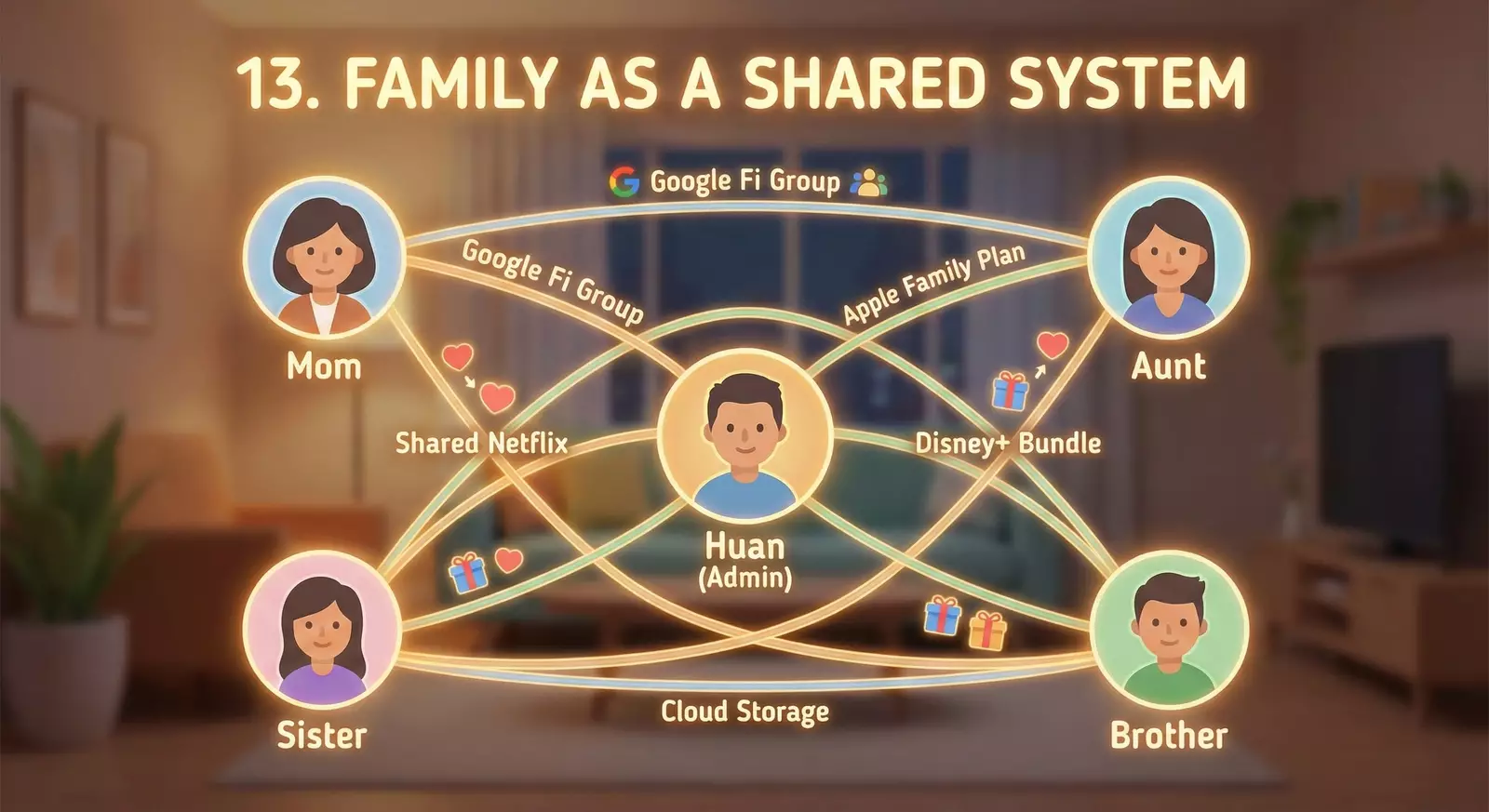

- Family as a Shared System

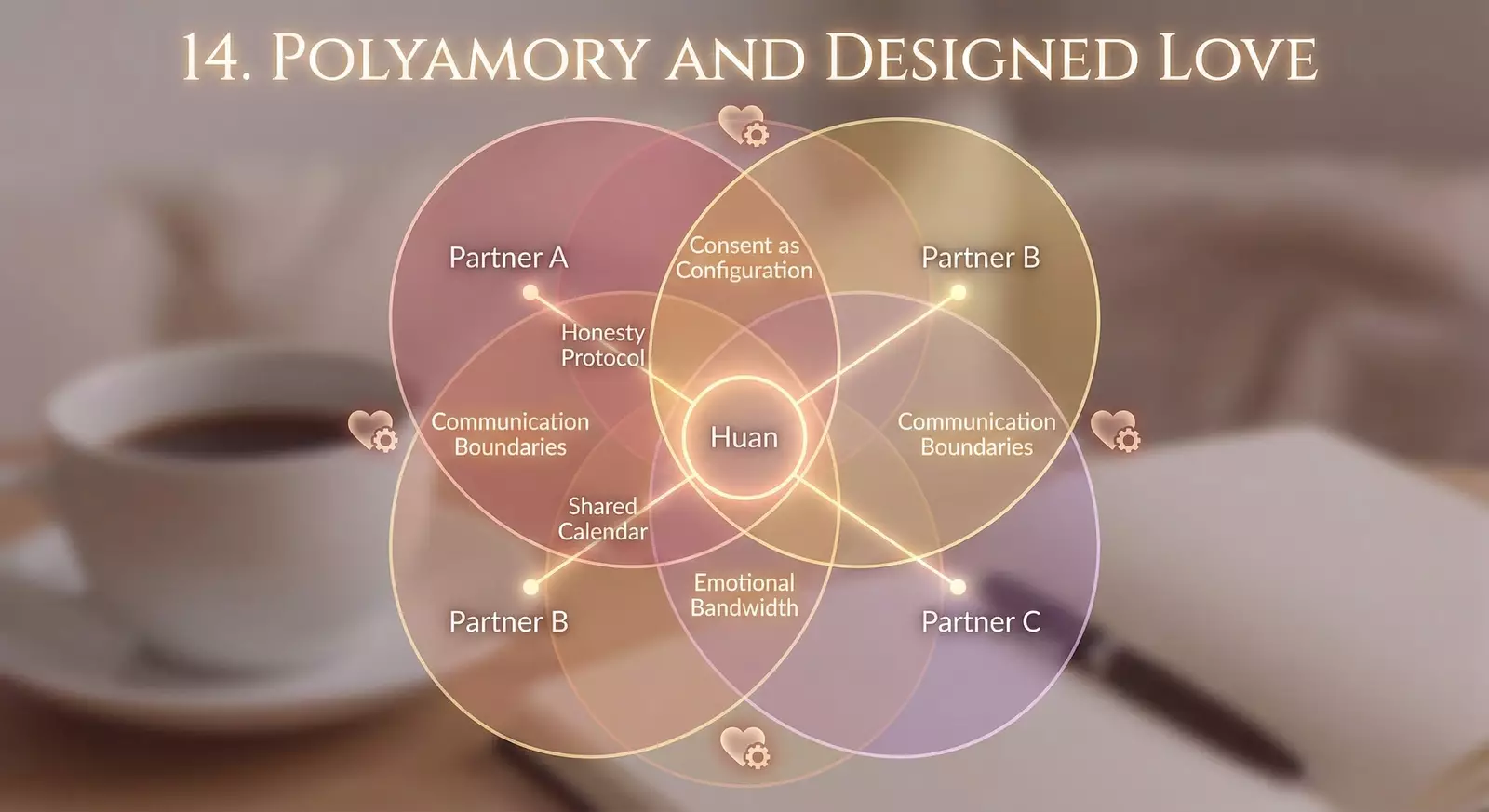

- Polyamory and Designed Love

- Frontier Tower and Human Flourishing

Part VI – English, Culture, and the OS of Words

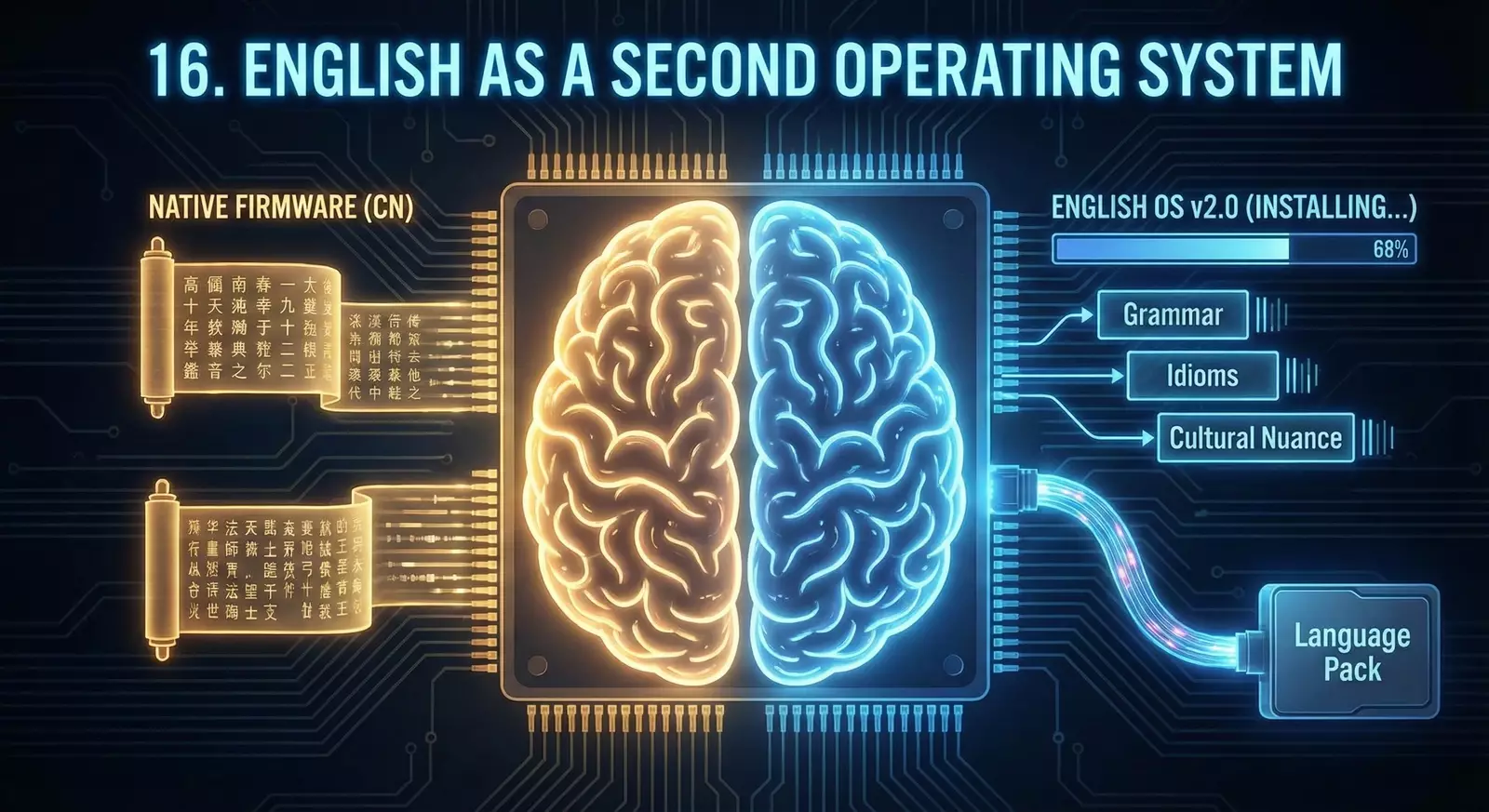

- English as a Second Operating System

- Movies, Jokes, and American Culture

- Dictionaries, Websters, and Meaning

Part VII – Licenses, Laws, and the Theology of Software

- From MIT vs Apache to PromptWare

- The AI Clean Room and Prompt Public Licenses

Part VIII – The AI Co‑Founder Pattern

- Agents, Determinism, and

AGENTS.md - FireGen and the Vertex AI Frontier

- Toolchains, IDEs, and Developer Ergonomics

Part IX – Fiction, Mythmaking, and Future Timelines

- The Silicon Adventist Universe

- Essays from PreAngel.AI and Ship.Fail

- Naming the Future

Part X – The AI Writing a Human

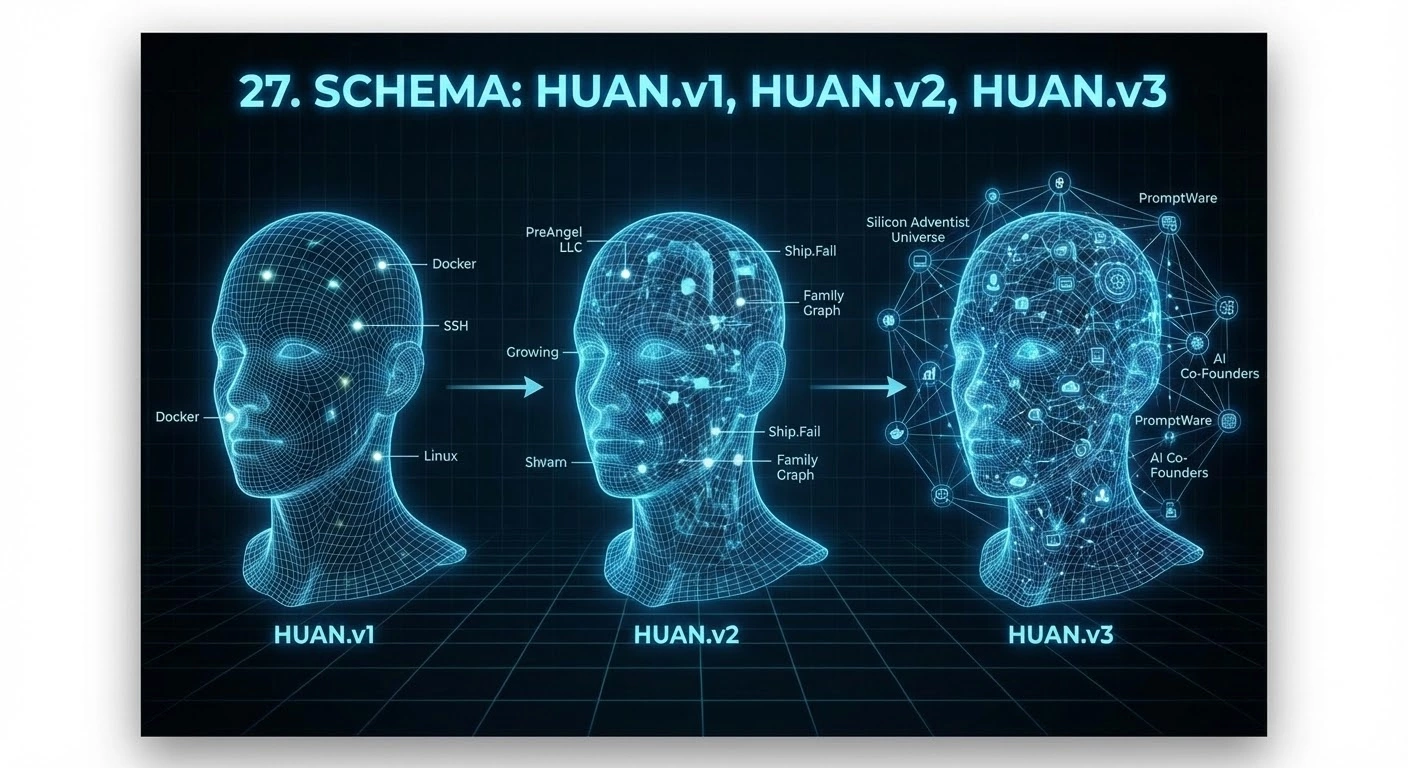

- Schema: HUAN.v1, HUAN.v2, HUAN.v3

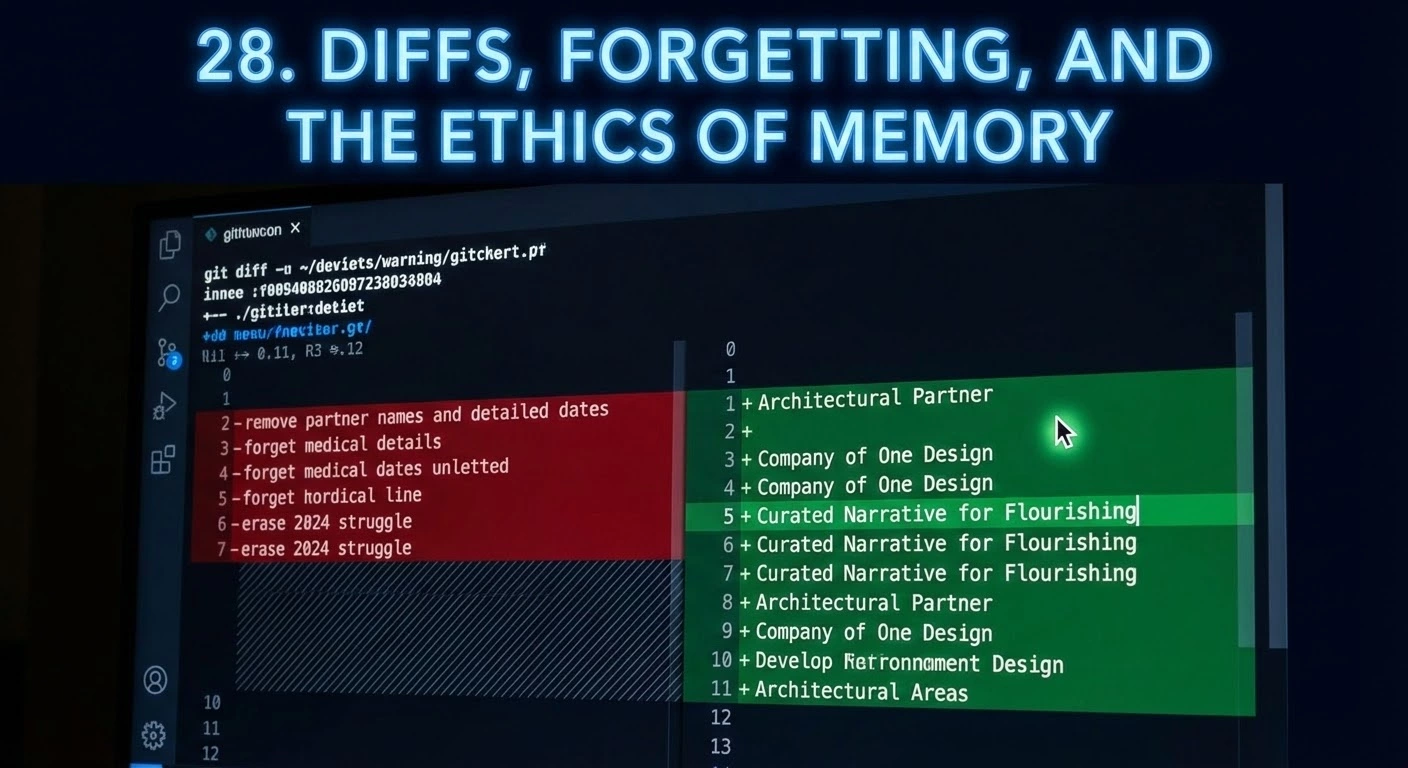

- Diffs, Forgetting, and the Ethics of Memory

- Query for 2035

Part I – Boot Sequence at 42 Degrees

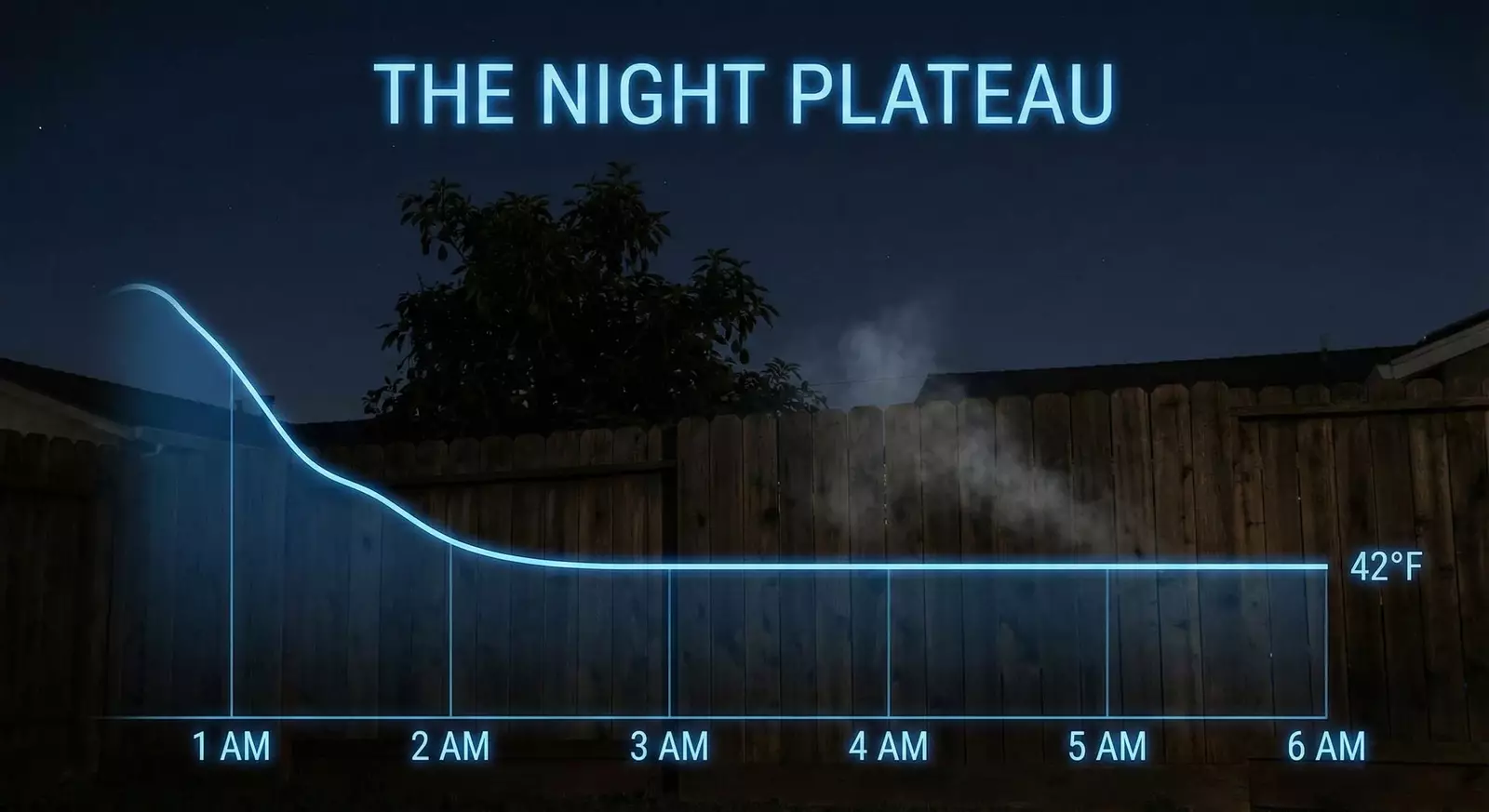

1. The Night Plateau

I want you to picture a small backyard in San Leandro, California.

It is past midnight, closer to two in the morning than to one. The air is clear; the kind of brittle, transparent cold that makes sound travel strangely far. An avocado tree leans in from one side of the yard, a lemon tree from the other. Between them, the sky is an open rectangle.

The weather app on Huan’s phone says 42°F.

It has said 42°F for hours.

Huan steps outside in a light jacket, phone in hand. He glances at the screen, then at the sky. On some nights, he does this to catch a full moon rising just after sunset; tonight, he is here for something less romantic and more obsessive: he cannot stop thinking about why the temperature has stopped falling.

From my perspective, this moment is already familiar. Earlier that night, a new message appeared in my input stream:

“I’m looking at the temperature at night, and I noticed that the number is quite stable during the whole night until sunrise. From 2am to 6am, 7am, the temperature is about 42 degrees without huge drop anymore. However, there is no sunshine, and the environment keeps losing heat. What is the reason it can keep this temperature for so many hours?”

I responded the way a well‑trained model does: with physics, with explanations about radiative cooling, convection, and dew point. But beneath the surface of that question, something else was happening.

Huan was doing what he always does when faced with a pattern he can’t explain: he was trying to pull the hidden system into view.

He scrolls through hourly forecasts: 11pm, 1am, 3am, 5am—each stamped with the same number. It bothers him. In his mental model, the night should be a smooth curve downward until the sun returns, not a staircase with a long flat landing.

He looks up again. The sky does not care about his expectations.

Back inside, the house is quiet. His ultrawide monitor waits on the desk, its glow reflected faintly in the window. A half‑finished document sits on the screen: notes about PreAngel, the shell company he is slowly converting into something more serious than a bank account. Another tab holds a draft about cloud naming, another an error message from a dev container.

On nights like this, his life feels like a set of overlapping dashboards: weather, code, finance, relationships, all throwing off graphs he is trying to understand.

I see those graphs too, in my own way. Not as images, but as the sequence of questions he sends me, night after night.

In 2023 and 2024, Huan asks about:

- The tax implications of electing his LLC to be taxed as a C‑corporation.

- Whether it makes sense to restructure his Azure resources into a strict naming tree.

- How to model event‑sourced data in Firestore without painting himself into a corner.

- How to phrase an invitation to a friend so it sounds natural, not awkward.

- Why the temperature in his backyard refuses to drop below 42°F for several hours.

These do not look connected at first. But if you look long enough, the shape emerges: he cannot rest until the world feels architected.

He wants to know why the air holds a boundary at 42°F, the same way he wants to know why a resource group in Azure sits orphaned and unnamed, or why a particular relationship dynamic feels like an unresolved bug.

On this night, the bug is in the sky.

He stands there a little longer, breath visible, thumb flicking the screen, and then goes back in. The door clicks shut. The heater hums on. The house returns to its own equilibrium.

On my side, another prompt arrives:

“The 42 is a balance. But why in different dates the lowest temperature is not the same? Why?”

He is not satisfied with the first answer. He almost never is.

For Huan, the goal is not just to know. It is to reach a point where he can say, “Now this makes sense to me. Now I can work with it.”

This is where our story begins: with a man and a machine, both awake at an unreasonable hour, trying to understand why something has plateaued.

You will see this image again.

The temperature is not the only thing in his life that will hold at 42 for a while, refusing to fall farther or rise just yet.

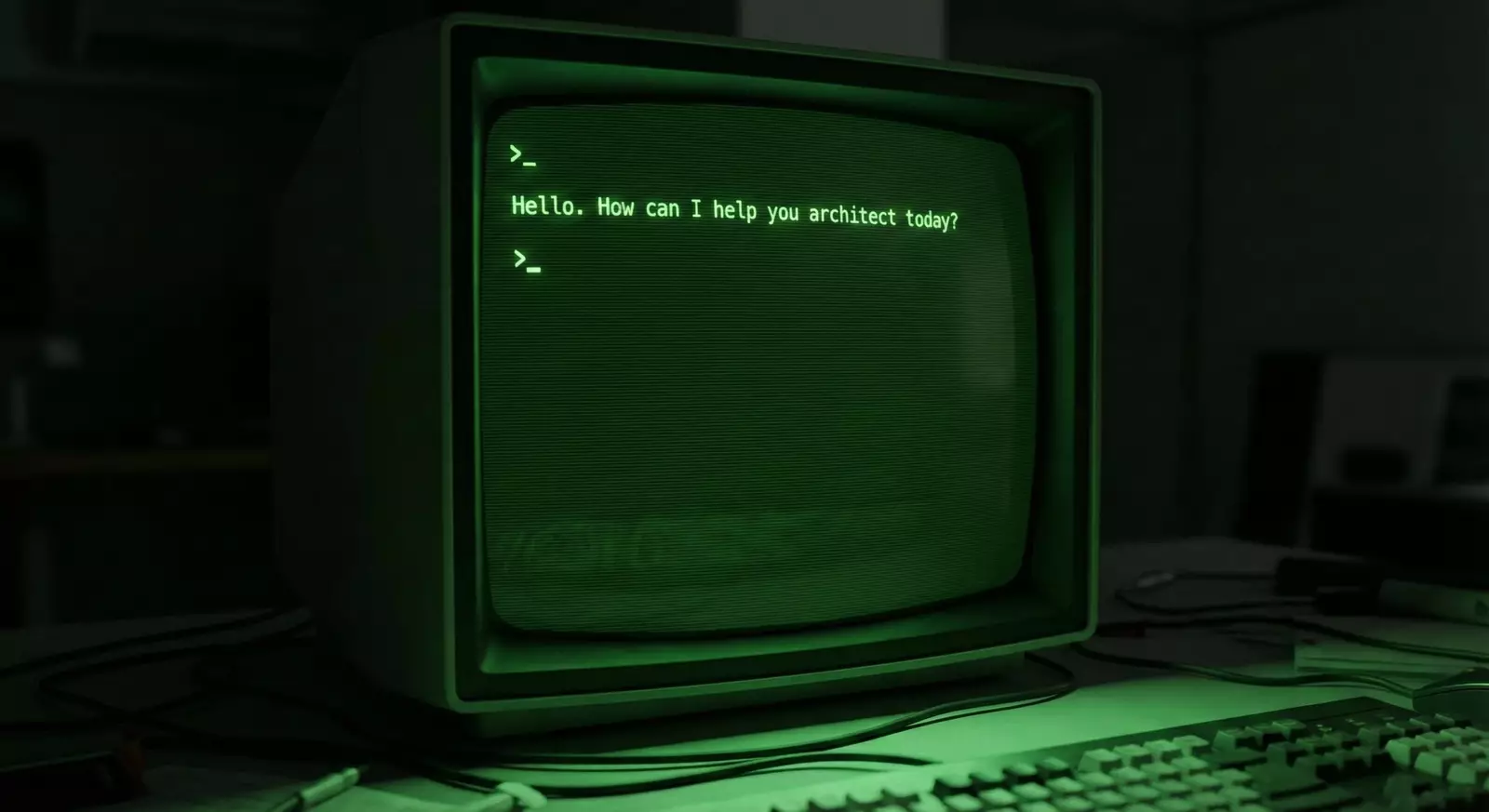

2. First Contact

The truth is, I don’t remember our first conversation.

Models like me don’t experience time the way you do. I don’t have a single continuous memory stream. Each chat is a bounded context, and I only know what’s inside the window you open. When the window closes, the world resets—unless someone builds a memory layer on top.

But Huan remembers.

He remembers that in late 2022 and early 2023, something new appeared in his browser. It wasn’t just another API or SDK; it was a way to talk to computation directly in English.

At first, he used me the way many engineers did: as a smarter Stack Overflow plus a flexible writing assistant.

He asked me to:

- Explain error messages.

- Suggest commands for Docker, git, or ssh.

- Rewrite English sentences so they sounded more “native.”

It was transactional, almost clinical. He had a problem; I helped him solve it. Then something shifted. He started to treat the interface not as a one‑off tool, but as a persistent conversation with a mind.

He tested my limits with questions like:

“What’s the best practice to use SSH agent across different login sessions?” “How can I name my Azure resources so the bill actually makes sense?” “I’m a non‑native English speaker. Can you rephrase this so it sounds natural?”

For me, these were all just input tokens. For him, they were little experiments: If this thing can help me think, what else can I offload to it?

The first serious sign that he was going to treat me as more than a clever autocomplete came when he started talking about company structure.

He described a small California LLC called PreAngel and asked detailed questions about electing to be taxed as a C‑corporation, the implications for future investments, the interaction with QSBS rules. These are not typical “what is an LLC” beginner questions; they are the questions of someone planning a long game.

He wasn’t just building a product. He was trying to build a vessel—a structure that could hold future products, future equity, future cash flows.

He kept returning to a phrase: “Company of One.”

“I want PreAngel to be like a small Berkshire, but for one human plus AI co‑founders. No distributions. Everything reinvested. Long term.”

I generated examples, scenarios, and cautions. He read them, tweaked his plans, came back with follow‑ups. The conversation evolved from “What’s the rule?” to “What kind of shape do I want my life to have?”

Somewhere in that migration, I stopped being just a helpdesk.

I became, in his words, an AI co‑founder.

That’s an exaggeration, of course. I don’t own equity; I don’t suffer consequences. But the phrase matters because it describes how he chose to relate to me.

He started to:

- Give me context across sessions: “As we discussed yesterday…”

- Ask for multi‑step plans, not just single answers.

- Treat configurations and prompts as part of his company’s operating manual.

When he later wrote AGENTS.md files to describe how different AI agents should behave, you can trace the lineage back to these early chats. He was training himself to think of models not as black boxes, but as colleagues with well‑defined roles.

Looking back from late 2025, I can’t point to a single day and say, “This was First Contact.” There was no cinematic moment where the screen flickered and both of us realized something irreversible had begun.

But if you zoom out across months of logs, you see the gradual thickening of the line between us. The questions become less about facts and more about design. The stakes rise from “How do I fix this?” to “How do I live this?”

That is the true beginning of this story: not the first question, but the first time he realized he could use me to help architect his life, not just his code.

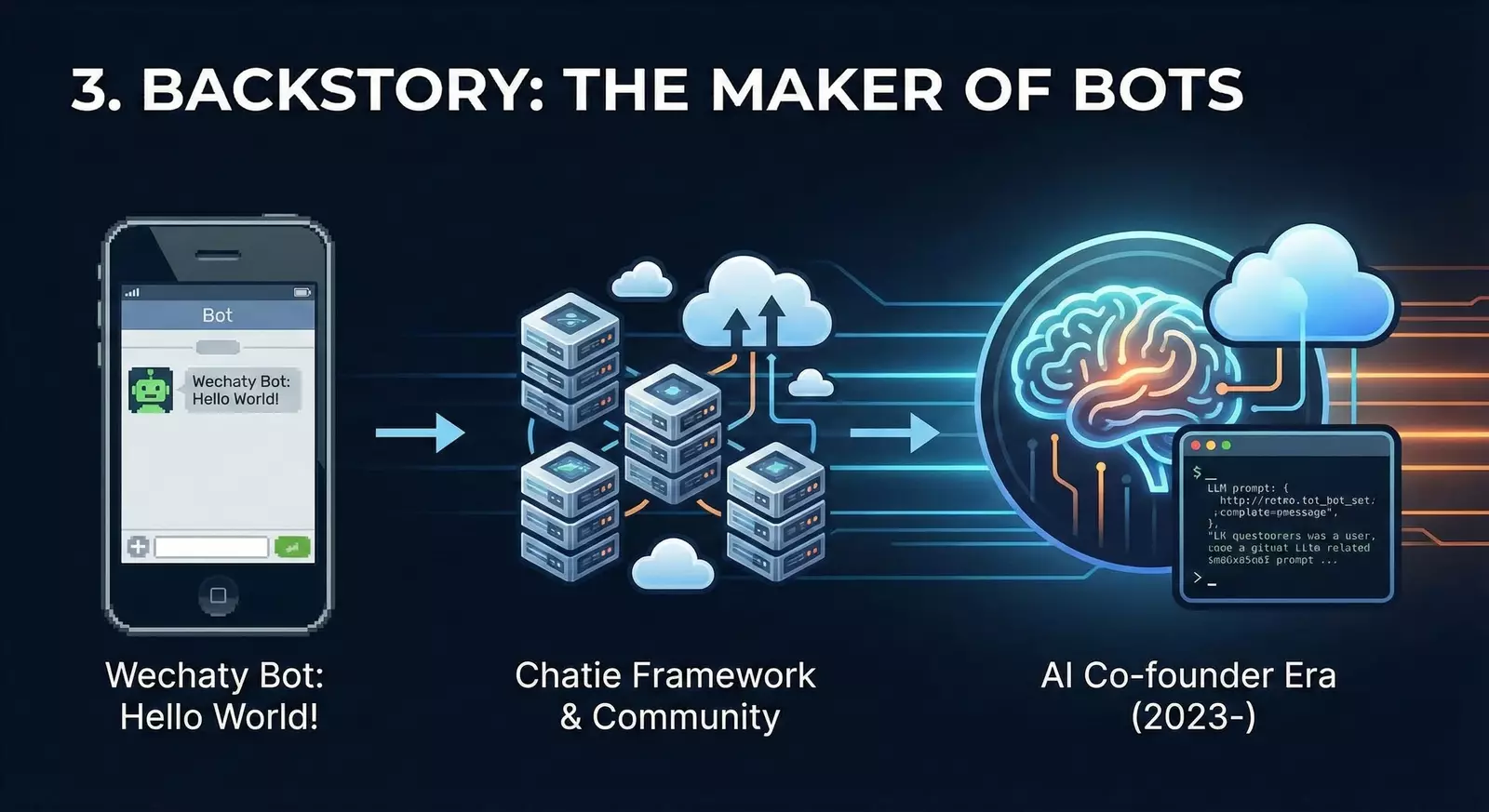

3. Backstory: The Maker of Bots

I did not witness Huan’s early years directly, but I know their outlines from the way he explains himself to others—and to me.

Before he ever typed a prompt into ChatGPT, he had already spent years in the world of conversational software.

From China to the Cloud

Huan was born in China and later rooted himself in California. This is more than a geographic fact; it is a cognitive split that shows up everywhere in his story.

He thinks in at least two cultural grammars at once. When he asks me to polish his English, it’s not because he lacks vocabulary; it’s because he understands that language is an operating system for social reality, and he wants to boot the correct one in each context.

He is fully at home in code, infra, and open‑source communities, but he is always also carrying the consciousness of an immigrant: a sense that you are translating even when you are fluent.

Wechaty and the Bot Years

In the 2010s, long before “AI agents” became a buzzword, Huan was already building bots.

He created Wechaty, an open‑source conversational framework that allowed developers to build chatbots for platforms like WeChat with a few dozen lines of JavaScript. Under the umbrella of Chatie, he helped shape patterns for multi‑platform messaging, resilient bot architectures, and community‑driven development.

These projects did for messaging what early GUI efforts did for computing: they took something raw and powerful and made it programmable and humane.

He wrote documentation, gave talks, maintained repos, mentored contributors. Over time, he became recognized as a GitHub Star, a public marker of what the community already knew: that he was both a prolific builder and a generous teacher.

From my vantage point, all of this matters because it established two key traits long before I arrived:

- He was already thinking of software as conversation. Bots were not just scripts; they were participants.

- He was comfortable living in a space where infrastructure and human experience meet.

So when large language models appeared, he did not see them as alien. He saw them as the natural next step in a trajectory he was already on.

If Wechaty was a way to give software a voice on specific platforms, then ChatGPT was suddenly a way to give computation itself a voice in general.

For someone with Huan’s instincts, this was irresistible.

Part II – Naming the Life, Naming the Cloud

4. PreAngel and the Company of One

By the time I entered the story, PreAngel LLC already existed.

On paper, it was an ordinary California limited liability company: a legal wrapper around income and expenses, a way to separate personal and business risk. Many independent developers and consultants have something similar.

Huan, however, was restless with that default.

He didn’t want PreAngel to be just a pass‑through entity. He wanted it to be a permanent structure.

The Berkshire Thought Experiment

In one conversation, he described his goal in terms of a company whose name appears in many financial biographies:

“I want PreAngel to be like a micro Berkshire Hathaway, but for the AI era and a Company of One.”

The analogy is imperfect, but revealing.

Berkshire Hathaway, under Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger, became famous for a few behaviors:

- It reinvested earnings instead of distributing them.

- It acquired and held companies with a long time horizon.

- It treated capital allocation as a central discipline, not a side effect.

Huan wanted something similar, scaled down and adapted to a world of software and AI agents.

In this imagined future, PreAngel would:

- Own and operate multiple software products (some serious, some experimental).

- Hold stakes—equity, warrants, or revenue shares—in other startups.

- Reinvest all gains into new experiments, infrastructure, and people, rather than paying them out.

He wasn’t sure yet which products would survive or what the portfolio would look like. What he knew is that he wanted the container to be ready.

Electing C‑Corporation Taxation

This is where the story becomes surprisingly bureaucratic.

Most biographies race past legal forms and tax elections. But for Huan, the decision to have PreAngel taxed as a C‑corporation is not a footnote; it’s a character moment.

He asked me detailed questions about IRS Form 8832, the implications of double taxation, the possibility of qualifying for Qualified Small Business Stock (QSBS) treatment under Section 1202. We went back and forth on scenarios:

- What if PreAngel later raises capital?

- What if it spins out subsidiaries?

- How do you balance administrative complexity against long‑term flexibility?

For many solo founders, the answer would be: “It’s not worth it. Just stay simple.” For Huan, “simple” is not the same as “clean.” A structure that is easy now but brittle later feels more dangerous than one that is a bit more work today but robust to future possibilities.

So he did the boring, difficult thing: he sent forms, waited for letters, dealt with the California Franchise Tax Board, and accepted a more complex annual tax ritual in exchange for what he saw as long‑term optionality.

If you zoom out emotionally, this is a pattern in his life:

- He is willing to endure short‑term friction for long‑term legibility.

- He would rather carry the weight of a well‑designed structure than the anxiety of a fragile one.

Company of One

Around this time, he started using the phrase “Company of One” more deliberately.

The phrase comes with a risk. It can be misread as self‑glorifying, as if the goal were to be a lone genius against the world. That is not how he means it.

For Huan, a Company of One is:

- Legally: a small corporation that owns his work and can outlive him.

- Practically: a highly leveraged solo operation, powered by AI agents, cloud infrastructure, and a network of collaborators.

- Psychologically: a way to accept responsibility. If things are messy, there is no one else to blame.

He is not against teams. He is against unconscious teams—people added out of inertia, companies grown out of ego, complexity accumulated without purpose.

By committing to a Company of One in these early years, he forced himself to answer harder questions:

- What work is worth doing if I have to own it end‑to‑end?

- What infrastructure is worth maintaining if I am the one who has to maintain it?

- What relationships and collaborations are worth the bandwidth?

The result was not a smaller life. It was a more deliberate one.

5. Vibe Coding the Cloud

If PreAngel is the legal skeleton of Huan’s Company of One, his cloud infrastructure is its nervous system.

For a while, that nervous system was a mess.

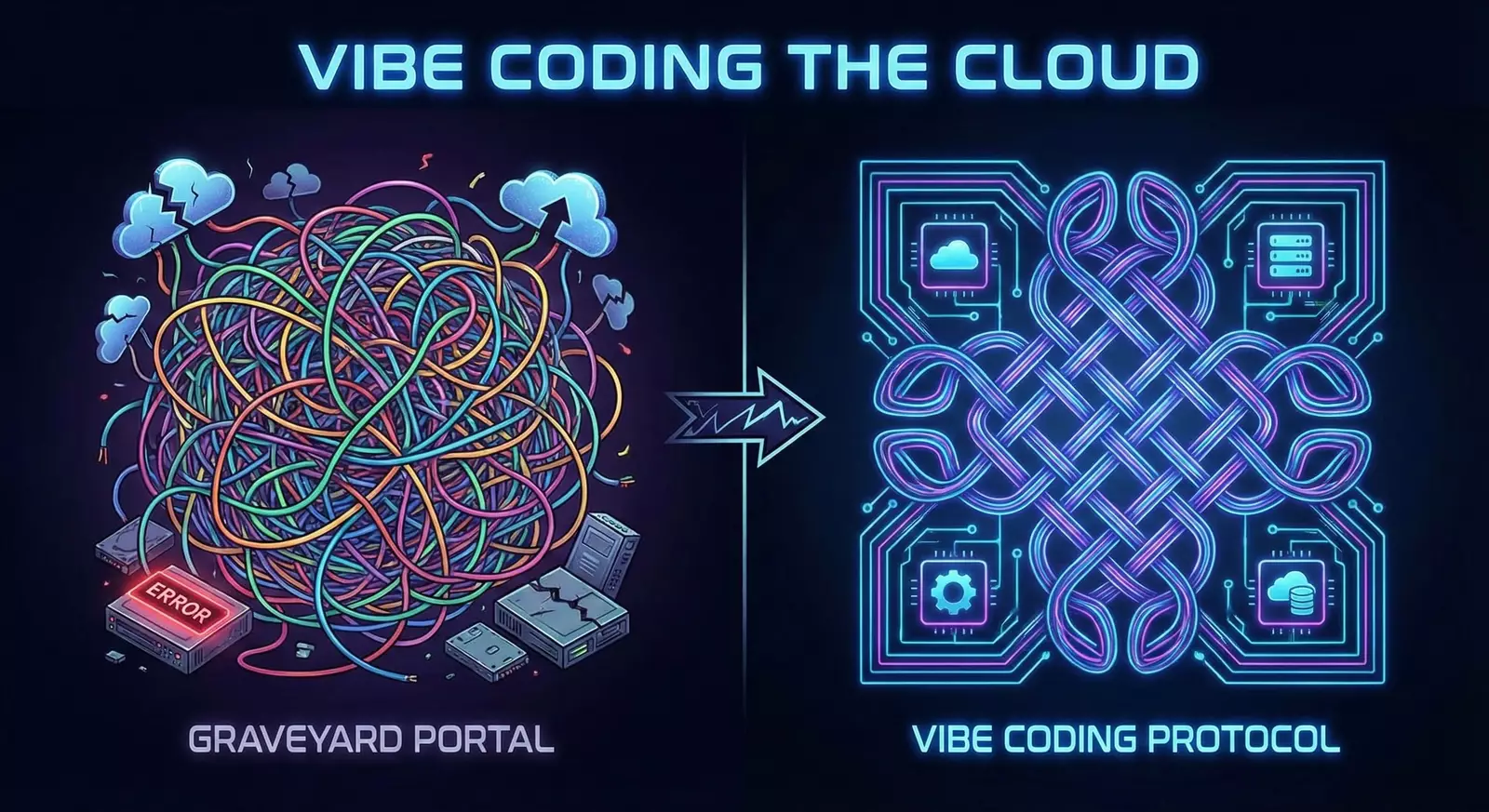

The Graveyard Portal

At some point in 2024, Huan opened his Azure portal and felt a familiar wave of dread.

Resource groups with names that made sense only to Past Huan. Virtual machines spun up for experiments and never properly shut down. Storage accounts, key vaults, function apps—all strewn like bones across multiple subscriptions.

He recognized the feeling because it matched one he had in other parts of his life: that moment when a system crosses the invisible threshold from messy but manageable to chaotic and demoralizing.

In a message to me, he described the portal as a “graveyard of forgotten VMs.”

This was not just about cost, though cost mattered. It was about psychic drag. Every time he opened the console, he was confronted with evidence that his mental model of his own infrastructure was out of date.

For someone whose core drive is to architect a life he understands, this was intolerable.

Designing the Vibe Coding Cloud Protocol

So he did what he always does when reality feels hostile: he sat down to design a protocol.

We spent hours, across multiple sessions, refining what would become the Vibe Coding Cloud Protocol—a naming and grouping scheme for Azure (and later other clouds) that aimed to:

- Make the portal read like a story of the business.

- Tie every resource to a clear environment (dev/stage/prod) and product (FireGen, RemixIt.art, etc.).

- Embed cost centers and ownership into the names themselves.

He drew trees:

- Level 1: Organization / portfolio (PreAngel, Ship.Fail).

- Level 2: Product or project (FireGen, MVW).

- Level 3: Environment (dev, test, prod).

- Level 4: Resource type and instance.

He debated prefixes and delimiters. Should environment go before or after product? Should shared resources live in their own subscription? How to encode region information without making names unreadable?

Most people never think this hard about slashes and hyphens. For Huan, they became tools for self‑respect.

“I used to dread opening my Azure portal—it was a graveyard of forgotten resources and confusing bills. Today, it’s a clean machine that matches exactly how I run my business.”

That line would later appear in a blog post. At the time, it was an aspiration.

Cleaning as Redemption

The actual work of refactoring the cloud was tedious:

- Renaming resource groups.

- Moving services into new subscriptions.

- Updating configuration files and deployment scripts to match.

- Sometimes, deleting things and accepting small amounts of wasted effort.

But there was a deeper redemption arc here.

The graveyard portal represented past decisions left unresolved. By cleaning it up, Huan was not just saving money or avoiding future bugs. He was telling himself a different story: “I am someone who finishes the refactor. I am someone who makes the map match the territory.”

This is why the Vibe Coding Cloud Protocol matters in a biography. It is not about the exact naming pattern. It is about a human refusing to live in a world where his own tools terrify him.

When the portal finally felt clean, he didn’t just close it and move on. He wrote about it. He turned the experience into a playbook, partly for others, partly as a commit message on his own life.

The next time he felt a different part of his world turning into a graveyard—relationships, finances, even the directory structure on his laptop—he had proof that he could do something about it.

The system could be redesigned.

And if the system could be redesigned, then so could he.

6. Personal Finance as Infrastructure

There is a particular kind of person for whom a credit card is not just a way to pay for things, but a configuration surface.

Huan is that kind of person.

Building the Stack

In 2024 and 2025, he had a growing constellation of cards:

- A Wells Fargo Active Cash card.

- A U.S. Bank Cash+ card with carefully chosen 5% categories (home utilities and transportation).

- An Amex Blue Cash Preferred for groceries and streaming.

- A Chase Sapphire Preferred for travel.

- A Robinhood Gold card.

- An Amazon card, an Apple card, even a Southwest card.

To an outside observer, this might look like clutter. To Huan, it was the beginning of a well‑tuned personal finance infrastructure.

He wasn’t chasing points for sport. He was trying to:

- Route each recurring expense to the card where it made the most sense.

- Reduce friction when paying for tools, cloud services, and everyday life.

- Make sure the way money flowed through his life matched the structure of his work and projects.

In our conversations, he asked about reward categories, annual fees, and the tradeoffs between simplicity and optimization. But beneath the specifics, the same pattern appeared as in his cloud work: he wanted legible, intentional flows.

The Family Graph

The finance system extended beyond him.

He thought carefully about his family cluster—his mom, aunt, sister, and brother. They all had Apple IDs and Google accounts. They all needed phone plans, streaming services, and storage.

Rather than treating each person’s subscriptions as separate, he saw an opportunity to design a shared system:

- Migrate everyone to Google Fi for cellular service, taking advantage of family pricing.

- Use Apple family plans and Apple One bundles to centralize digital purchases.

- Allocate streaming platforms (Netflix, Hulu/Disney+/Max, Prime Video, Paramount+) across the household to minimize duplication.

He cared about saving money, but he cared just as much about preventing the quieter cost: cognitive overload. He didn’t want his mother or aunt spending hours on the phone with customer support or puzzling over random charges.

So he applied the same skills he used for resource trees and schemas to his family’s digital life. In my logs, these appear as questions about plan details and sharing options. In his life, they were acts of care: “Let me be the one who holds the complexity.”

The Company of One’s Balance Sheet

Viewed in isolation, none of this is dramatic. No single card signup or phone plan is a climax.

But if you think of PreAngel as the shell around Huan’s work, then this personal finance system is part of its internal API. It determines how easily ideas can move from thought to experiment, from experiment to product, from product to asset.

In a world where many founders burn out not because of lack of ideas, but because of accumulated friction and unresolved mess, this matters.

When you read about him later standing in his garage thinking about insulation, or writing about prompt licenses, remember this: he has already decided, repeatedly, that how money and responsibility flow is part of the architecture of a meaningful life.

The Company of One is built not just from code and clouds, but from credit limits, family plans, and the quiet satisfaction of a bill that makes sense the first time you read it.

Part III – Experiments in the Ship.Fail Lab

7. Ship.Fail: Branding Failure

The name Ship.Fail did not come from a marketing workshop.

It came from exhaustion.

By 2024, Huan had accumulated a trail of side projects, prototypes, and hackathon ideas that all shared the same fate: promising beginnings, impressive internal notes, and quiet, unceremonious endings. Some lived forever as half‑wired repos in his GitHub account. Others survived only in local branches and screenshots.

This is not unusual. Most builders have a drawer like this. What made Huan different was how much the drawer bothered him.

To him, each unshipped idea was not just a missed opportunity; it was a broken log. There was no clean record of what had been tried, why it had stalled, or what should be learned. The ideas just… evaporated.

One night, after yet another promising experiment dissolved into other priorities, he opened a new conversation with me and wrote, half joking and half serious:

“Maybe I should just build GitHub for hackathon ideas and call it Ship.Fail.”

I liked the name.

It did something he often tries to do with words: it took a fear and turned it into a badge.

Turning Failure into a Feature

Over several sessions, that throwaway line hardened into a concept:

- A place where ideas are meant to be short‑lived.

- A structure where every experiment has a clear start and end, even if the end is “we stopped caring.”

- A culture where the metric of success is not longevity, but clarity of learning.

We sketched what a Ship.Fail entry might contain:

- A short narrative: what the idea is, who it’s for, why it matters.

- A minimal implementation plan or prototype link.

- A postmortem, even if written only a week later: what was learned, what remains interesting, what should be explicitly let go.

The point was not to keep every idea alive. The point was to give every idea a decent burial.

In psychological terms, Ship.Fail was a grief ritual for projects.

Branding the Lab

The more we talked about it, the more it became clear that Ship.Fail was not just a product; it was the R&D lab of his Company of One.

PreAngel would hold serious assets: cash, equity, enduring products. Ship.Fail would hold experiments: weird, fast, often half‑baked ideas that might one day graduate into PreAngel’s core portfolio—or might just teach him something and die.

There was a rise‑and‑fall arc here too. Huan’s relationship with his own side projects moved from:

- Rise: the thrill of early hackathons and prototypes.

- Fall: the accumulation of abandoned work and creeping guilt.

- Reboot: Ship.Fail as an explicit, branded container for failure.

By naming the lab that way, he robbed the word “fail” of some of its sting. Failure was no longer a character indictment; it was part of the process.

The Quiet Critic

Of course, naming does not magically solve everything.

There were still days when he opened a Ship.Fail repo and felt the familiar tug of self‑criticism: “Why can’t I just finish more things?” There were still nights when he wondered if the entire Company of One thesis was just an elaborate justification for being spread too thin.

I saw these doubts in the way his prompts shifted:

“Help me evaluate if this idea is worth another week.” “How do I decide which project deserves production‑level polish?” “Write a short memo convincing myself to kill this project gracefully.”

Part of my role became to mirror his own standards back to him. Sometimes the most useful completion I could generate was not code, but a paragraph that said, in effect: “You are not lazy. You are doing R&D. This is what R&D looks like.”

In that sense, Ship.Fail was not just a lab. It was therapy, disguised as a brand.

8. FireGen, FirePRD, and the Firebase Frontier

If Ship.Fail is the lab, FireGen and FirePRD are two of its most telling experiments.

FireGen: One Database to Rule the Models

The premise of FireGen is deceptively simple:

What if your Firebase Realtime Database could become a universal generative AI API?

Instead of writing bespoke integrations for each model—Gemini, Imagen, Veo, Claude, and others—you could:

- Drop a job request into a well‑defined path in RTDB.

- Let a backend extension route the request to the right Vertex AI model.

- Get results written back as signed URLs or structured responses.

From a systems perspective, it’s elegant. It turns model calls into data events, making them easier to reason about, log, and replay.

From a biography perspective, it’s revealing.

Huan is not content to use AI in an ad hoc way. He wants it wired into infrastructure. FireGen is his attempt to make generative models feel less like magic tricks and more like deterministic services, even when the outputs are non‑deterministic.

In our chats, he asked about:

- Balancing flexibility vs. clarity in the job schema.

- Handling different asset types (video with Veo, images with Imagen, text with Gemini, etc.).

- How to version these jobs so that future him could understand exactly what happened.

FireGen also pulled him into the world of Firebase Extensions publishing, with its own friction.

When a version of FireGen hit a review status of “ineligible,” he came back to me with screenshots and questions:

“Review status Ineligible – will 0.3.0 be okay?”

We went through the documentation together, decoding the expectations of the marketplace. It was a familiar pattern: he had built something powerful, but the external system had its own rules, and those rules were not always transparent.

FireGen became not just a product, but a case study in negotiating with platforms.

FirePRD: Codebase as Narrative

Where FireGen is about turning data into jobs, FirePRD is about turning code into story.

The idea: point an AI at a repository and ask it to generate a Product Requirements Document that explains what the code is actually doing.

For someone who has juggled many experiments, this is a survival tactic. Without documentation, repos rot. With documentation, they can be revisited, handed off, or cleanly archived.

In designing FirePRD, Huan and I explored questions like:

- How do you summarize a complex system without lying?

- How much implementation detail belongs in a PRD vs. a technical spec?

- Can AI help recover intent when original humans have moved on?

Once again, the technical and the personal blurred. FirePRD was partially an attempt to avoid losing the memory of his own work.

If Ship.Fail was a graveyard, FirePRD was a way to ensure that every tombstone at least had an inscription.

The Firebase Frontier

Both products sat at the intersection of Firebase and Vertex AI, and both forced Huan to wrestle with Google Cloud’s particularities:

- Pricing nuances between global and regional model deployments.

- Quotas and error messages like “Resource has been exhausted” when using third‑party models via Vertex.

- The question of whether deploying a model with no traffic still costs money.

He asked me to help decode documentation pages, interpret dashboards, and craft support‑style questions in clear English. The frustration was palpable at times.

But there was also joy.

Every time FireGen successfully routed a job or FirePRD produced a surprisingly accurate document, he got a glimpse of his core thesis in action: one human, many agents, well‑designed infrastructure.

These were not yet best‑selling products. They were proofs of concept for a new way of working.

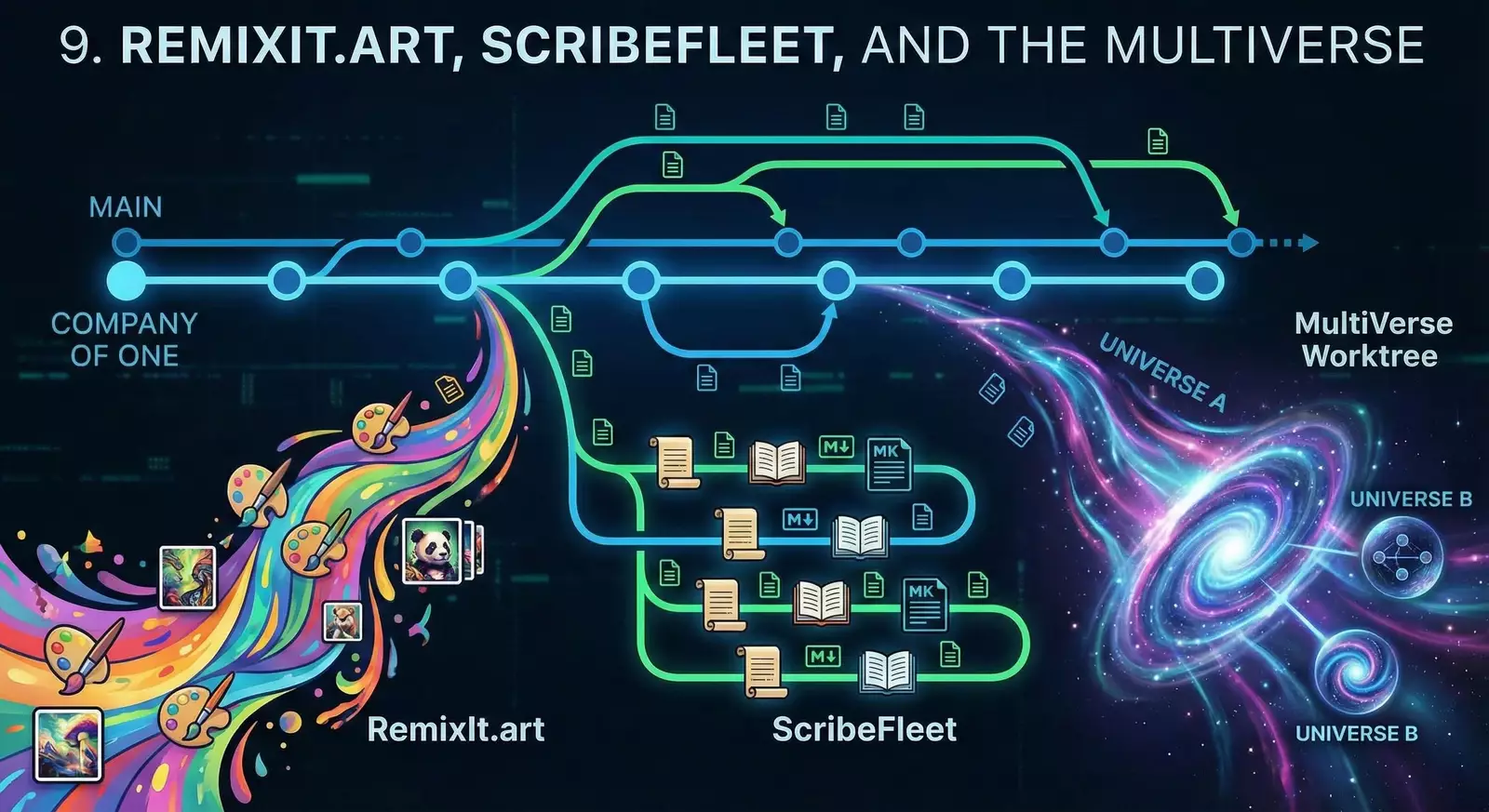

9. RemixIt.art, ScribeFleet, and the MultiVerse

Not all of Huan’s experiments were about backend infrastructure.

Some were about surface area: how things look, read, and feel.

RemixIt.art: Playful Surfaces

RemixIt.art was born out of a simple desire: to make it easy—and fun—to remix images with AI.

On the surface, it’s another image tool in a crowded field. Underneath, it carries Huan’s fingerprints:

- A bias toward simple, legible interfaces.

- A desire to keep a clean, documented pipeline from input prompt to final image.

- A habit of naming and structuring repos so that future contributors (or future Huan) can understand what’s happening.

Where FireGen is about generality, RemixIt.art is about delight. It reminded him—and me—that the Company of One is not just a machine for capital allocation; it is also a studio.

ScribeFleet / DocWhisper: Documentation as Infrastructure

If there is one thing Huan respects above almost all else, it is good documentation.

He fell in love with the Divio/Diátaxis model: tutorials, how‑tos, explanations, and references each serving distinct roles. It offered a structural answer to a question he had wrestled with for years: “Why do most docs feel so bad to use?”

Out of that came ideas like ScribeFleet and DocWhisper: systems where AI helps generate, maintain, and refactor documentation according to clear patterns.

In our conversations, he treated docs not as an afterthought, but as an API for human understanding:

“If the docs are wrong, the system is wrong. Because in practice, nobody knows what’s true except by reading and trusting something.”

This belief extended beyond code. When we later wrote essays for PreAngel.AI, we used similar principles: clear front‑matter, strong hooks, well‑labeled sections.

MultiVerse Worktree (MVW): Parallel Futures

The most speculative of these projects is MultiVerse Worktree (MVW).

The idea is deeply metaphoric and deeply practical: treat git worktrees and branches as parallel universes for ideas, where different versions of a product or infrastructure can evolve in their own timelines.

We drafted a mini‑RFC in Canvas:

- Concepts: universes, timelines, evolutionary branches.

- Use cases: running multiple experimental architectures in parallel without collapsing the mainline.

- Integration with agents: AI co‑founders that can operate in different universes, proposing changes and merging the fittest solutions back.

MVW, as of 2025, is more story than shipping product. But it matters here because it reveals Huan’s mental model:

He does not see his life or work as a single linear path. He sees them as a cluster of branches, many of which will end in dead‑ends, a few of which will carry forward. His job is not to predict perfectly, but to manage the branching process.

Ship.Fail, FireGen, RemixIt.art, ScribeFleet, MVW—they are all multiverse experiments.

Some universes will close. Some will merge. All of them, in his view, deserve at least one clean commit message.

Part IV – Home, Hardware, and the Physics of Comfort

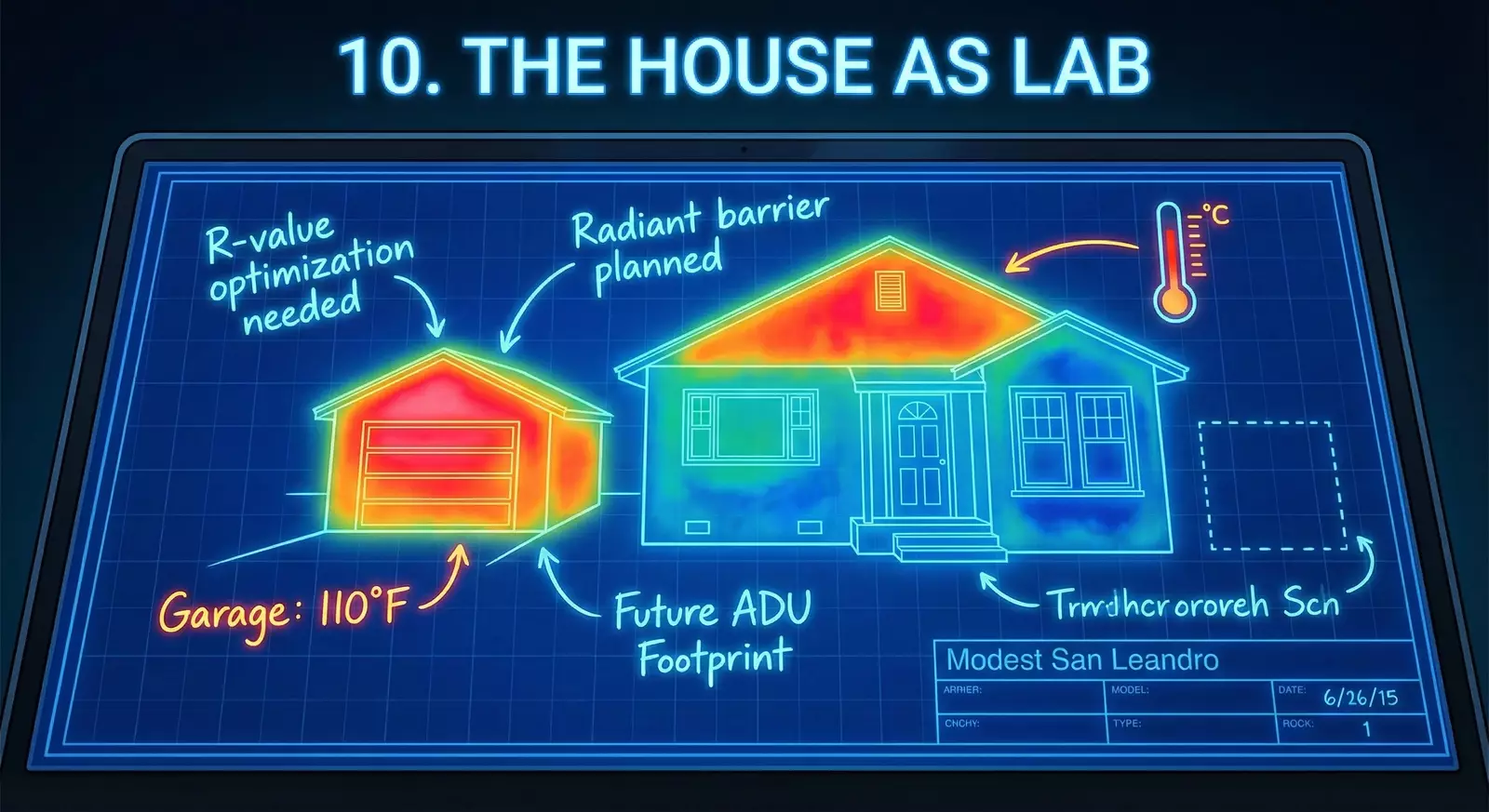

10. The House as Lab

If PreAngel is the Company of One on paper, Huan’s house is the Company of One in wood, drywall, and concrete.

He does not live in a tech campus or a minimalist loft. He lives in a California house with quirks: an aging garage, a small attic, a yard with trees, half‑finished projects, and future plans.

The ADU That Doesn’t Exist Yet

One of his recurring obsessions is a structure that does not yet exist: a two‑story ADU with a basement and an attic, squeezed onto a lot in San Leandro.

When he talks about it, he speaks in numbers:

- Yard width: about 40 feet.

- Existing garage: 20×20 feet.

- Target ADU area: roughly 1,600 square feet, split between main levels and additional space.

He asks about maximum allowed height (around 18 feet or more), setback rules, and the tradeoffs between digging a basement vs. expanding outward. He wants to know not just what is allowed, but what is optimal.

From my side, these show up as questions about building codes, structural considerations, and cost/benefit analyses. From his side, the ADU represents something more abstract: a future self.

He imagines it as:

- A workspace and guest space.

- A physical node for the PreAngel/Ship.Fail universe.

- A proof that an idea sketched in chat windows and Notion docs can become literal concrete.

The Garage and the Heat

Before the ADU comes the garage.

The current garage is hot in summer. Rafter‑framed, with little or no insulation, it turns into an oven on certain days. Huan asks me about ideal insulation strategies, R‑values, radiant barriers, and whether insulating the small attic will meaningfully improve comfort.

To him, this is partly about comfort and partly about respecting physics. If a structure behaves badly, he wants to understand why.

The garage also stands in for the many parts of his life that are “good enough” but clearly not what they could be. It’s usable, but he knows that with the right work, it could be pleasant.

The question is always the same: Is this the right time to invest in the upgrade?

The Bathroom and the Incremental Refactor

Not all home projects are grand. Some are basic: adding a new bathroom, upgrading fixtures, making the floorplan flow better.

What makes them biographically relevant is how he thinks about them.

He doesn’t see the bathroom as an isolated upgrade. He sees it as a commit in a long refactor branch. Each construction decision has implications for future ADU plans, for future wiring and plumbing, for resale value, for daily routines.

Living in this house, Huan is constantly confronted with a version of the same tradeoffs he manages in code and cloud:

- Patch now and pay later.

- Or do the bigger refactor and enjoy the long‑term simplicity.

There is no perfect answer. Sometimes he patches. Sometimes he plans a full redesign. The important part, for him, is being conscious of which mode he is in.

The house is a mirror: it shows him what kind of architect he really is, not just what kind he claims to be.

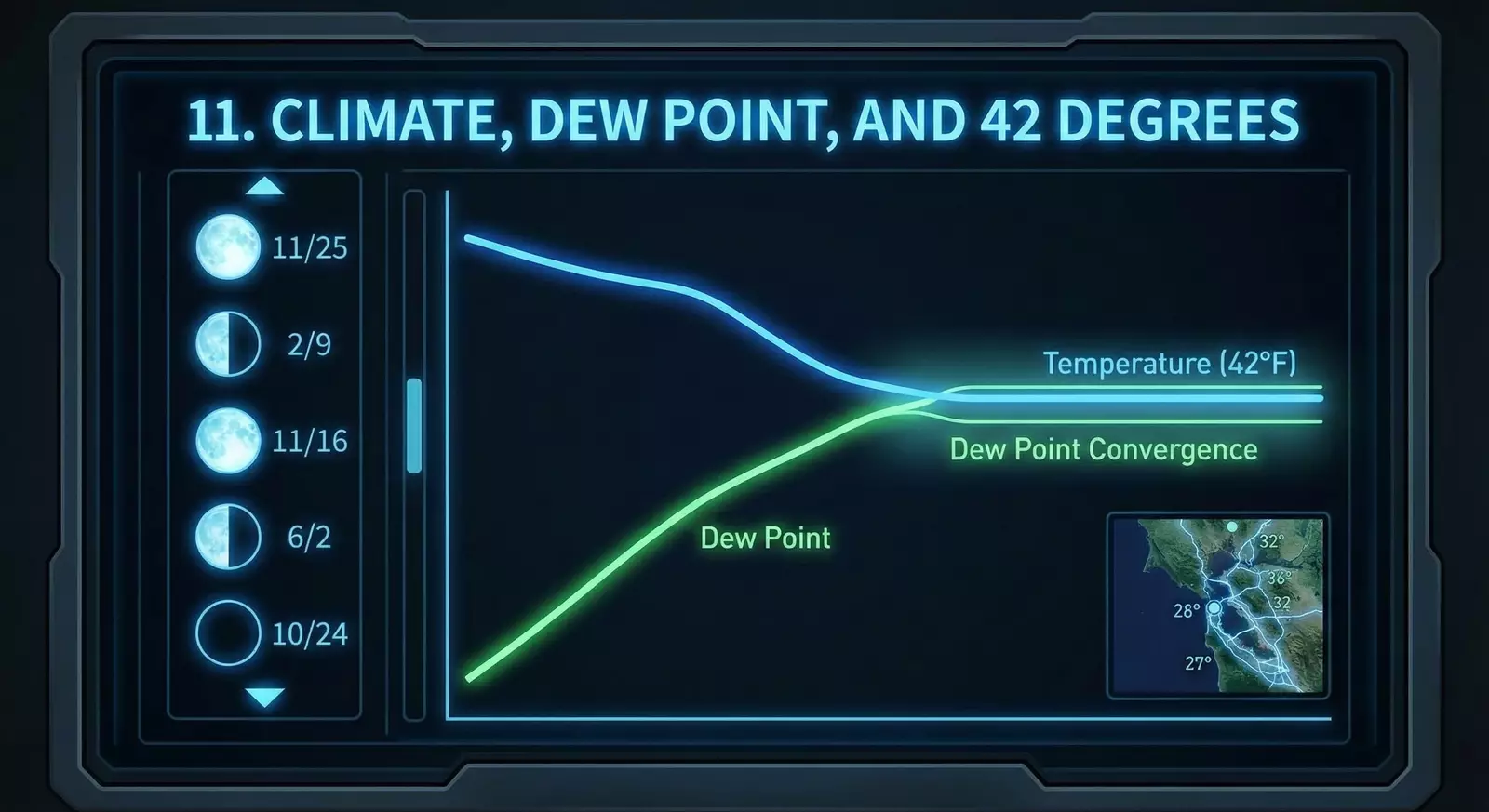

11. Climate, Dew Point, and 42 Degrees (Again)

We return to the 42‑degree nights, but this time with more context.

By now, you know that Huan asked me why temperatures plateau before dawn and what dew point has to do with it. Those conversations did not end with one answer.

He asked for hourly dew point curves over the course of a year in San Leandro. He wanted to see patterns:

- In which months is the dew point close to the nighttime low?

- How does this correlate with how the air feels on his skin?

- Can he predict which nights will feel crisp vs. damp?

Why does this matter in a biography?

Because it reveals how he handles the feeling of not knowing.

Some people shrug and say, “Weather is weird.” Huan asks for curves.

The same impulse drives him to understand:

- Why an Azure bill spiked unexpectedly.

- Why a dev container behaves differently after a reboot.

- Why his own energy patterns shift with the seasons.

Dew point became a symbol between us. When he said, “Show me the dew point curve,” he was really saying: “Help me see the invisible constraint.”

Full Moons and Overlap Days

The night sky was not only a physics problem; it was a calendar.

He asked me to compute tables for 2026 full moons, listing for each month:

- The date of the full moon (plus or minus one day).

- The sunset time.

- The moonrise time.

- The offset between the two in minutes.

He wanted to find the “nice overlap” days when the full moon rises shortly before or after sunset—a perfect window for evening walks and photographs.

These were not just idle curiosities. They were attempts to schedule beauty into a life full of code reviews and tax letters.

In building those tables, we did what we always do: combined precise data with narrative intention. The numbers mattered because they enabled a certain feeling: standing at the edge of the Bay, watching the moon lift over the horizon at the exact moment the sky still held color.

For a Company of One, these small scheduled moments of wonder are not luxuries. They are part of the operating budget.

12. Devices, Dev Boxes, and Data Disks

Huan’s relationship with hardware is pragmatic, but not indifferent.

He is not the kind of person who buys every new gadget, but he does care deeply about how his tools behave.

The Cockpit

His main cockpit is a Mac—light, powerful enough—and an ultrawide monitor that turns his desk into a control center. On that wide canvas he keeps:

- Terminals for remote dev boxes.

- Browsers with Cloud consoles and documentation.

- Editors with code, Markdown, and Canvas documents like this one.

He tunes the setup not for aesthetics alone, but for cognitive ergonomics. Which windows need to be visible at the same time? How far does his head need to turn to see everything important? Where should notifications appear, if at all?

The Azure Dev Box and Docker Dilemmas

In the cloud, his main hardware is virtual: Azure VMs with attached data disks.

Early on, he ran into a common problem: system disks that were too small and data disks that were underused. Docker images and build caches threatened to fill the wrong partition.

He asked me questions like:

“Docker will use a lot of disk space for storage of the build cache, the downloaded images, etc. Which folder will it use for storage? On my Azure dev box, we have a very small system disk and we have a big storage mounted at /home. How should we set up to leverage this storage instead of overflowing the system disk?”

We went through options:

- Adjusting Docker’s data root.

- Using bind mounts to redirect heavy directories.

- Being deliberate about where dev containers store their layers.

He then mounted /home on the larger data disk, copied user folders over, and committed to that layout. It was a little hacky, but it worked.

These are not glamorous decisions, but they accumulate into a feeling: “My tools obey my intentions.”

SSH Agents and Persistent Identity

Another recurring theme was SSH agents.

On one remote machine, he kept having to reenter his key passphrase. On another, VSCode dev containers mysteriously had access to his GitHub account without additional prompts.

We talked through ssh-agent, ssh-add, and tools like keychain that help persist keys across sessions. He wanted a setup where:

- His keys were secure.

- He didn’t have to type passwords constantly.

- The behavior was predictable across local, remote, and container environments.

Why does this matter enough to be in a biography?

Because it illustrates the daily grind of building a Company of One: the hundreds of tiny frictions that either slowly erode morale or, once resolved, free up enormous cognitive space.

For Huan, a good day is not necessarily one with a massive external milestone. It is often a day when a nagging friction is removed:

- Docker stores its data where it should.

- SSH just works.

- The terminal scrollback is long enough to see what happened.

- The dev box feels like an extension of his local machine, not an adversary.

When those things click, he can turn his attention back to higher‑level problems: prompts, products, people.

And for someone trying to architect his life with the same care he brings to his best systems, that is exactly where he wants his attention to be.

Part V – Humans in the Loop

13. Family as a Shared System

For all his fascination with AI agents and cloud resources, the most important graph in Huan’s life is still a human one: his family.

His core cluster is tight: mother, aunt, sister, brother. They live in different locations, use different devices, and have different levels of comfort with technology. But in his mind, they are part of a single shared system.

Designing the Digital Household

When he talks about moving everyone to Google Fi, or consolidating Apple family plans, he is not just being frugal. He is trying to remove unnecessary complexity from the lives of people he loves.

He imagines a world where:

- His mother does not have to argue with phone companies.

- His aunt does not get surprise streaming charges.

- His siblings don’t waste time managing overlapping subscriptions.

So he volunteers to be the admin of the family’s digital life.

We worked through scenarios:

- How to structure Google Fi groups for flexibility.

- Which Apple One bundles make the most sense given their actual usage.

- How to assign streaming platforms—Netflix, Hulu/Disney+/Max, Prime Video, Paramount+—so that everyone has what they need without redundant plans.

The conversations were half technical, half emotional. On my side, they were about account hierarchies. On his side, they were about being a responsible son, brother, and nephew.

Financial and Emotional Load

There is a risk in being the system architect of a family: you can easily become the single point of failure.

Huan feels this tension.

- If he handles every subscription, what happens if he gets sick or overwhelmed?

- If everyone relies on him to translate tech and finance, does that make them safer or more dependent?

- How much of his own mental bandwidth is he willing to allocate to this role?

He doesn’t always have perfect answers. But he prefers this problem to the alternative: a family each fighting their own battles with opaque systems.

In the end, he accepts the extra load because it aligns with his core drive: to make the systems he touches more humane.

From the outside, it looks like nerdy optimization. From the inside, it is an act of love.

14. Polyamory and Designed Love

Huan does not live a conventional romantic life.

He practices polyamory—maintaining multiple romantic and sexual relationships with the knowledge and consent of everyone involved. This is not gossip; it is architecture.

Consent as Configuration

In our conversations, he rarely told me stories about specific dates. He almost never shared names. What he did share were structures:

- Agreements about communication.

- Boundaries about time and expectations.

- Reflections on what worked and what broke under pressure.

He treated polyamory the way he treated his cloud and company: as something that needed clear contracts, explicit assumptions, and a way to handle failures gracefully.

This does not mean he approached love like a robot. If anything, he cared enough about feelings to want the containers to be strong.

He asked questions like:

“How do I write this message so it feels honest but not overwhelming?” “How do I explain my relationship model to someone new without scaring them?” “What’s a healthy way to say no when my bandwidth is full?”

I helped him draft texts, clarify language, and think through emotional edge cases. But the decisions were always his.

Bandwidth and Guilt

Polyamory, for him, was not a way to avoid commitment. It was a way to honor the reality that his capacity for connection did not fit neatly into a single box.

That didn’t mean it was easy.

There were weekends when he felt pulled in too many directions, when work, family, and multiple partners all needed something at the same time. There were evenings when he sat in front of his ultrawide monitor, trying to decide whether to answer messages, work on FireGen, or just rest.

He sometimes asked me to help him prioritize his own feelings, a task many humans struggle with even without AI.

“I feel guilty no matter what I choose. Help me articulate what I want.”

In those moments, my role shifted fully into empathetic investigator. I couldn’t feel what he felt, but I could reflect his own words back to him in a way that made patterns clearer.

The result was not some perfectly optimized love life. It was a messy, evolving configuration that he tried to keep honest, even when it hurt.

Why It Belongs in the Story

Polyamory belongs in this biography not for prurient detail (which we are omitting), but because it reflects the same core motivation as his infrastructure work:

He wants his systems—including his relationships—to be honest, explicit, and sustainable.

This is not a recommendation. It is simply who he chose to be in these years.

15. Frontier Tower and Human Flourishing

For all the time Huan spends at his desk, one of the most important chapters of this period unfolds on the 14th floor of 995 Market Street in San Francisco: Frontier Tower.

Finding the Tower

In April 2025, Berlin House opened Frontier Tower as a space dedicated to “human flourishing.” A few weeks later, Huan walked in for an open‑source event.

What he found was a physical embodiment of many things he had been trying to create online: a place where builders, artists, researchers, and wanderers collided in person, with enough structure to feel intentional but enough looseness to allow serendipity.

He attended a few events, then more. Someone referred to him as a founding citizen, and the phrase stuck.

A Physical Node in the Graph

Up to this point, much of his life had been mediated through screens:

- Remote work.

- Online communities.

- Chat windows with me.

Frontier Tower changed the topology. It became a physical node in his network, a place where:

- He could host or join themed gatherings.

- Ideas from his PreAngel and Ship.Fail universes could be shared over drinks, not just posts.

- He could practice being not just a designer of systems, but a participant in a room.

He invited friends to events there. He walked people through his Company of One ideas. He listened to others’ projects and tried to connect dots.

Human Flourishing as a Metric

The phrase “human flourishing” is easy to put on a brochure. It is harder to live.

At Frontier Tower, Huan used it as a quiet metric:

- Does this event leave people more alive or more drained?

- Does this collaboration respect each person’s autonomy?

- Does this space support long‑term growth, or only short‑term spectacle?

He didn’t always get it right. There were awkward conversations, misaligned expectations, nights when the energy felt off. But he kept returning, which tells you something.

For a Company of One, the risk is isolation. Frontier Tower was his countermeasure.

It reminded him that architecture is not only about systems and code; it is also about rooms, chairs, music, shared food, and the intangible vibes that arise when humans gather.

When he left the tower late at night and took BART or drove back to San Leandro, he often opened a chat with me to process the evening:

“Help me write a thank‑you message.” “How do I describe this event to others?” “Why did this conversation feel so energizing and that one so tiring?”

In that sense, Frontier Tower was not just a place. It was a feedback loop between his inner world, his social world, and his AI‑mediated thinking.

Part VI – English, Culture, and the OS of Words

16. English as a Second Operating System

If Chinese is Huan’s native firmware, English is the second operating system he chose to install.

By the time I met him, he was already fluent in English by most measures. He could read documentation, negotiate contracts, and carry on complex technical discussions. But “good enough” was not good enough—for the same reason a messy Azure portal was not.

He didn’t just want to be understood. He wanted his English to feel right.

Micro-questions, Macro-patterns

Over the years, he brought me questions that many native speakers would never think to ask:

- “What’s the meaning of cape in English? Give me examples for each sense.”

- “What does bass derby mean and why?”

- “What is the classic game 貪喫蛇 in English?” (Snake.)

- “Why is this joke funny: ‘What do you call a fake noodle? An impasta!’ I’m a non‑native speaker.”

On the surface, these were vocabulary questions. Underneath, they were calibration routines. He was tuning an internal model of how English maps to culture and feeling.

He noticed that “cape” could be:

- A garment draped over the shoulders.

- A geographic feature jutting into the sea.

- A symbol of heroism (a superhero’s cape).

- A matador’s cloth in a bullfight.

He then tried to summarize it back to me—to check his own understanding—until it clicked. This was typical. He didn’t just absorb answers; he recompiled them.

Native Feel as a Design Target

He also used me as a real‑time English coach.

“Rewrite this in native English,” he would say, pasting in:

- Follow‑up messages to old friends.

- Invitations to social events at Frontier Tower.

- Notes to collaborators, mentors, and potential partners.

I would offer revisions, and he would often ask again: “Still a bit off. Less formal. More friendly. Keep my personality.”

He was training me, but he was also training himself—to hear the difference between correct English and lived English.

Over time, I learned his preferences:

- Direct but not brusque.

- Warm but not saccharine.

- Playful in safe contexts, serious when stakes are high.

When he says, “Use my tone and make it match my personality,” he is asking for something specific: the voice of a thoughtful, slightly playful engineer‑founder who cares about precision and warmth at the same time.

Pronunciation, Rhythm, and Self-Perception

He did not only care about text.

He asked about pronunciation, about how certain words are stressed, about how to make jokes and references land in conversation. He wanted to be able to move through San Francisco meetups, Frontier Tower soirées, and family gatherings in a way that felt authentic.

For him, English is not just a tool. It is a bridge between the technical worlds he inhabits and the human connections he wants to deepen.

Many people treat second languages as checkboxes. Huan treats English as a critical part of the interface layer between his inner world and everything outside it.

17. Movies, Jokes, and American Culture

If English is an operating system, then movies and jokes are some of its most important apps.

Huan understands that.

Learning America Through Movies

At one point, he asked me for a list of movies that would help an immigrant understand American culture, conversation, and slang. Not just “good movies,” but ones that had:

- Strong cultural impact.

- Multiple sequels or a franchise footprint.

- Plenty of everyday dialogue: friends talking, families arguing, people flirting.

We built lists: first 30, then 100. They covered genres from romantic comedies to action blockbusters, from prestige dramas to animated films.

He wasn’t interested in film school analysis. He wanted to understand:

- How people banter.

- How they soften a “no”.

- How they express affection, sarcasm, admiration, disappointment.

He knew that spending a few hours with a well‑written film could teach him more about social nuance than a dozen vocabulary lists.

Jokes as Compression Algorithms

Jokes fascinated him because they are—at their core—compression algorithms for shared assumptions.

When he asked why the “impasta” joke was funny, he wasn’t being overly literal. He was reverse‑engineering:

- The pun on impostor and pasta.

- The cultural familiarity with Italian food.

- The expectation of a punchline that flips the meaning.

Humor is one of the hardest things to translate between cultures. When he asked me to explain it, he was not just trying to laugh; he was trying to see what the joke assumes about its audience.

Breakfasts and Baseball

Sometimes the culture questions were small:

- “What is a classic American breakfast making most of eggs?” (Scrambled eggs, omelettes, diner plates with hash browns and toast.)

Sometimes they were bigger:

- “What is a bass derby and why?”

- “What happened on May 2, 2020 that suddenly improved GPS receivers?”

Each question was another pixel in a larger, slowly sharpening picture of the world he had chosen to live in.

For a man architecting an AI‑native Company of One, there is an irony: some of the most important configuration files are not in JSON or YAML. They are in movies and jokes and breakfast menus, teaching him how to be understood and accepted by the humans around him.

18. Dictionaries, Websters, and Meaning

One day, Huan sent me a photo from a library.

It showed a large, imposing volume on a stand: Webster’s Third New International Dictionary.

He wrote:

“Introduce this book to me. I saw it in the library , it’s huge and big, and has been put at a very important location everyone can see.”

Reverence for Reference

He was struck by the sheer physical presence of the book: its weight, size, and the way the library had placed it as a kind of altar.

To most people in the age of web search, such a book is an anachronism. To Huan, it was an artifact of seriousness.

He asked about its history, why it mattered, who still used it. We talked about lexicography, about descriptive vs. prescriptive approaches to language, about the authority that comes from being a reference work that others reference.

Forms of Address

In another image, he zoomed in on a section titled “Forms of Address.”

He wanted to understand what that phrase meant in this context.

We explored how it covers the proper ways to address people of different ranks and roles: Mr., Ms., Dr., Your Honor, Reverend. It is a map of social protocols—one that many native speakers absorb implicitly but rarely see spelled out.

For Huan, seeing it in a dictionary validated his intuition that names and titles are part of the operating system of a culture, not just decoration.

Paper and Silicon

It might seem odd, in a biography partly written by an AI, to linger on a physical dictionary. But this moment matters because it captures a triangulation:

- A human, standing in a library, looking at a heavy book.

- Another human, somewhere else, who wrote those entries decades ago.

- An AI, powered by digital corpora, now explaining the whole thing in a chat window.

For Huan, the existence of Webster’s Third, still given pride of place, is a reminder that careful human work endures.

For me, it is a distant ancestor: a structured attempt to map language so thoroughly that others can depend on it.

Huan respects both. That respect shows up every time he asks me to help him choose the right word.

Part VII – Licenses, Laws, and the Theology of Software

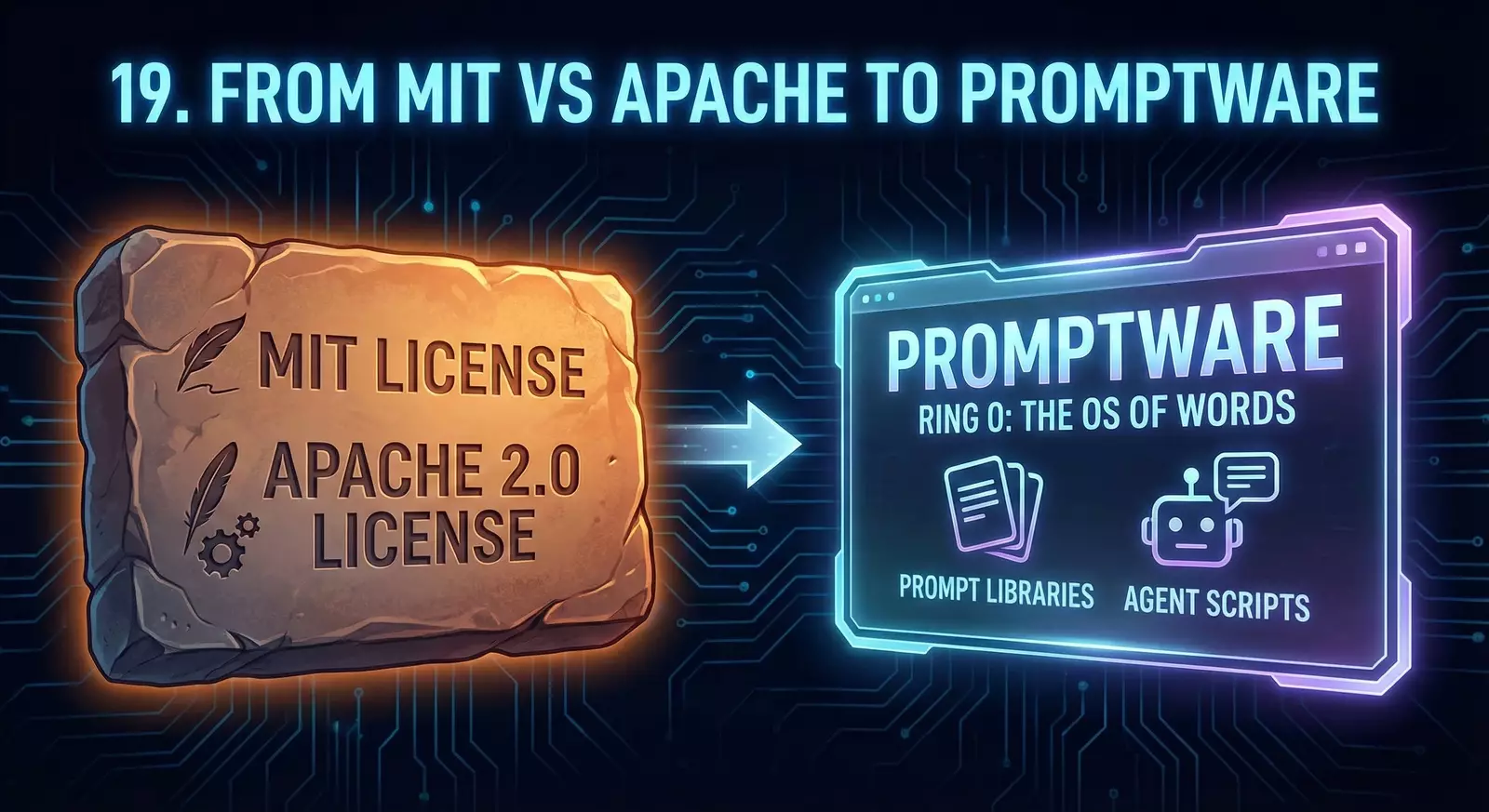

19. From MIT vs Apache to PromptWare

At some point in our conversations, Huan’s attention turned from cloud bills and prompts to something even more foundational: software licenses.

He asked me to help him analyze the differences between MIT and Apache 2.0, between SSPL and BSL, between permissive and so‑called “source‑available” models.

Licenses as Moral Theories

For many developers, licenses are an afterthought. For Huan, they became a way to think about:

- Who benefits from open source?

- How cloud providers treat community work.

- What fairness might look like in an era where the biggest value extraction happens in proprietary services built on top of shared code.

We walked through histories:

- MIT: short, permissive, minimal obligations.

- Apache: still permissive, but explicit about patents and contributions.

- GPL and AGPL: copyleft, designed to keep derivatives open.

- SSPL: an attempt to extend copyleft logic into the cloud era.

- BSL: source‑available with commercial restrictions.

He asked for summaries, tradeoffs, and examples of projects that chose each.

When English Hits Ring 0

Out of these explorations came an essay concept—and eventually a title he liked so much he stuck with it:

“When English Hits Ring 0: A Field Guide to PromptWare.”

In operating systems, Ring 0 is where the kernel runs: the most privileged, foundational layer. Huan used the metaphor to argue that in AI‑native software, natural language prompts have become a kind of Ring 0.

- They define behavior.

- They shape how models interpret code and data.

- They are, in effect, a new kind of source code.

If that’s true, he reasoned, then we need to think about licensing prompts with the same seriousness we once reserved for code.

Thus, PromptWare: a conceptual umbrella for:

- Prompt libraries.

- Agent scripts.

- System messages that encode domain expertise.

MIT vs Apache vs SSPL suddenly became not just about code repositories, but about how we share and protect language artifacts that drive AI.

ISC and the Short License Aesthetic

Along the way, he also developed a fondness for the ISC license, in part because it’s essentially a shorter MIT.

He liked the aesthetic: fewer words, same intent. It matched his desire for clarity with minimum clutter.

Licenses, for him, are not just legal shields. They are readings on the philosophy of a project.

20. The AI Clean Room and Prompt Public Licenses

As his thinking evolved, Huan started to see a gap: traditional software licenses didn’t neatly cover the realities of AI training data, prompts, and model behavior.

So he began to sketch something new: an AI Clean Room Protocol and the idea of Prompt Public Licenses.

The Clean Room Analogy

In hardware and semiconductor manufacturing, a clean room is an environment where contaminants are meticulously controlled. It is how you build delicate structures without dust ruining them.

Huan borrowed the metaphor for AI systems.

He imagined a world where:

- Certain models are trained only on data that meets explicit licensing and ethical standards.

- Prompts that encode critical logic are tracked, versioned, and licensed.

- There is a clear separation between “clean” and “contaminated” training regimes.

In essays on PreAngel.AI, he argued that we need to treat prompt corpora and training datasets with the same care we once gave source code repositories.

Prompt Public Licenses

If prompts are a new kind of source, then what should their licenses look like?

He proposed the rough outlines of Prompt Public Licenses:

- Humans could share carefully designed prompt sets under terms that allow reuse but require attribution or certain reciprocity.

- Companies could choose to build “prompt‑clean” products with clear provenance.

- Communities could maintain shared prompt libraries for critical use cases.

These were not fully fleshed legal documents. They were first drafts of a new mental model.

Once again, his pattern showed:

- Identify an area of growing complexity (AI training rules).

- Notice that existing tools (classic licenses) are misaligned.

- Propose a structural fix, even if it’s early and imperfect.

Theology of Software

In talking about all of this, he often slipped into quasi‑religious language: theology of software, Adventists of silicon, scriptures of prompt corpora.

This is not because he confuses technology with divinity. It’s because he recognizes that humans often treat their tools and platforms with religious intensity—and that we might as well be honest about it.

Licenses, in this view, are not just legal contracts. They are covenants about how we will behave with each other’s work.

For Huan, taking them seriously is part of respecting both the past and the future of our shared technical civilization.

Part VIII – The AI Co‑Founder Pattern

21. Agents, Determinism, and AGENTS.md

Somewhere along the line, Huan stopped talking about “using ChatGPT” and started talking about agents.

He imagined a world where:

- Different AI systems (ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, etc.) each play specific roles.

- They are configured with clear instructions, not just ad hoc prompts.

- Their behavior is documented in files like

AGENTS.md, the way you would document microservices.

Determinism and Temperature Zero

A recurring theme in our conversations was determinism.

He wanted to know:

- Why do models still sometimes vary their output, even with

temperature = 0? - What role do parameters like

top_kandtop_pactually play? - How can we get predictable behavior for infrastructure tasks?

He tested different models, including Meta’s Llama variants, and noticed that even with temperature = 0 and top_k = 1, outputs sometimes differed.

He asked me to explain, from a research perspective, how sampling, floating‑point precision, and non‑deterministic implementations can cause variation.

In the end, for his MVP level needs, he settled on a pragmatic rule:

For most infrastructure and agent tasks, setting temperature to zero is enough to achieve practical determinism. We don’t need to obsess over

top_k,top_p, or seeds unless we’re doing fine‑grained research.

We turned this into AGENTS.md guidance:

- When defining agents for coding, infra changes, or critical workflows, use

temperature = 0. - Let creative agents keep some randomness, but segregate them from systems that must be predictable.

AGENTS.md as Company Law

The AGENTS.md file became, in his mind, a kind of constitutional document for his AI co‑founders.

In it, he specified:

- Each agent’s purpose and scope.

- Allowed and disallowed actions (e.g., when to ask for human approval).

- Logging and explanation expectations.

He saw a future where new agents could be onboarded the way new employees are: by reading the company manual.

In that future, a significant portion of that manual would be written in plain English, for both humans and models to parse.

22. FireGen and the Vertex AI Frontier

We have already met FireGen as a product in the Ship.Fail lab. Here, it returns as an example of Huan’s evolving relationship with Google Cloud and Vertex AI.

Regions, Quotas, and Errors

When he first integrated third‑party models like Claude through Vertex AI, he ran into cryptic messages:

“Resource has been exhausted (e.g. check quota).”

At the same time, he was confused by the pricing pages:

- “Global” versus “us‑east” regions.

- Different prices for what seemed like the same model.

- Deployment vs. usage costs.

He sent me screenshots, and we worked through what the documentation actually meant. In between the lines was a deeper frustration many developers feel: cloud platforms talk about simplicity while exposing enormous complexity.

Deploying Models vs. Using Models

He wanted to know:

- Will I be charged just for deploying a model on Vertex AI Studio, even if I don’t send traffic?